I think of this domain as a lot of the “nuts and bolts” of teaching. These are approaches that will vary dramatically among teachers but ultimately that all work to serve the same goal of staying on top of all of the day-to-day demands of the profession. At the same time, it’s important to devise systems that allow for some sort of work-life balance. On this page I’ve provided some details of how I tackle these demands as well as the thought process behind those choices.

Professionalism | Executive Functioning

This category is an area in which I feel that I have systems that work effectively for me. Although I sometimes feel overwhelmed by my various responsibilities, at the end of the day I have confidence in my organizational systems and approaches, and I know that I will always be able to push through. That being said, I also recognize that my friends and colleagues have different systems and I appreciate being able to learn more about their approaches, as much of what I do has been cobbled together over time from others’ strategies.

(1) approaches recommendations for improvement receptively and responsively

As is true for probably any profession, there is always room to improve one’s practice, even after many years. I am definitely mindful of the fact that these opportunities exist and the need for me to be open to feedback, whether that’s from supervisors, colleagues, or students. One challenge is how to receive constructive or even critical feedback without reacting defensively or pushing back. I know that I have a tendency to want to explain my thinking, but I’ve been working on resisting that impulse, and instead just receiving that feedback and really trying to think deeply about it. This feels connected to that idea of intent vs. impact–at the end of the day I have to acknowledge that things don’t always work as planned or land as intended, and to be able to grow I need to hear that feedback, even though it can be uncomfortable.

Teaching Marine Biology with Adam Waltzer this year has been a great opportunity in this regard. I had taught the class six times before collaborating with Adam, and wanted to be sure to give him the chance to offer modifications or suggestions to the course.

Adam has had great suggestions about various aspects of the class, from student work to writing tests to grading, and I’ve learned a lot through this collaboration. In order for this to work, though, I had to loosen my grip a bit on what I thought of as “my” class and be open to hearing suggestions and constructive criticism.

“I have had innumerable professional interactions with Katie over the years and have always found these interactions respectful and productive. In developing curriculum for the Marine Biology upper school elective, Katie was interested in my perspective. She was curious and open to suggestions regarding age-appropriate workload and content. Since implementing that curriculum, we have had frequent discussions about assessment, pedagogy and classroom management.”

Adam Waltzer

A specific example of a suggestion comes to mind. Although it happened fairly early in my time at EPS, a recommendation that Sam made stuck with me and has since been incorporated into my repertoire. Namely, rather than saying “Does anyone have any questions?” I instead say, “What questions do you have?” As Sam explained it, this communicates to the students that I not only welcome, but anticipate questions and (hopefully) makes them more willing to seek clarification.

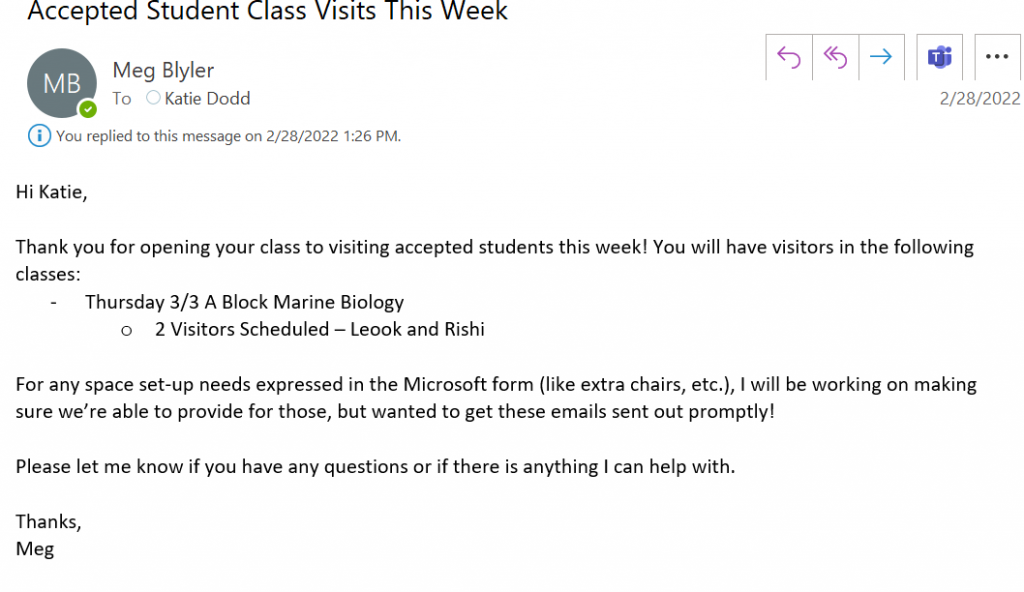

(2) displays openness and comfort with visitors observing class

Over the years I have found my confidence increasing when it comes to having others in my classroom. Having student visitors (most often students applying for admission) has always felt comfortable and I’ve been happy to try to help them get a sense of the school and of how we teach Science at EPS. This has happened slightly less often since my appointment shifted away from 6th grade, as there are fewer applicants for 7th grade. Now I tend to have more visitors in my Upper School classes.

In my first few years of teaching, I was very self-conscious about being observed by colleagues and would often doubt my ability to answer questions or discuss topics when I felt that there was an “expert” teacher in the room. In some ways this has gotten easier simply by increased frequency–a sort of “desensitizing” process. Sharing classrooms and lab spaces means it’s pretty typical for another science teacher to access the classroom while I’m teaching, and I hardly notice these “interruptions” at this point. Another thing that has probably made this feel a little easier is that I have also recognized the power of modeling that you DON’T have all of the answers, and that it’s okay to say “I don’t know” to a student question–it doesn’t reflect negatively on my expertise to admit that in front of adult visitors.

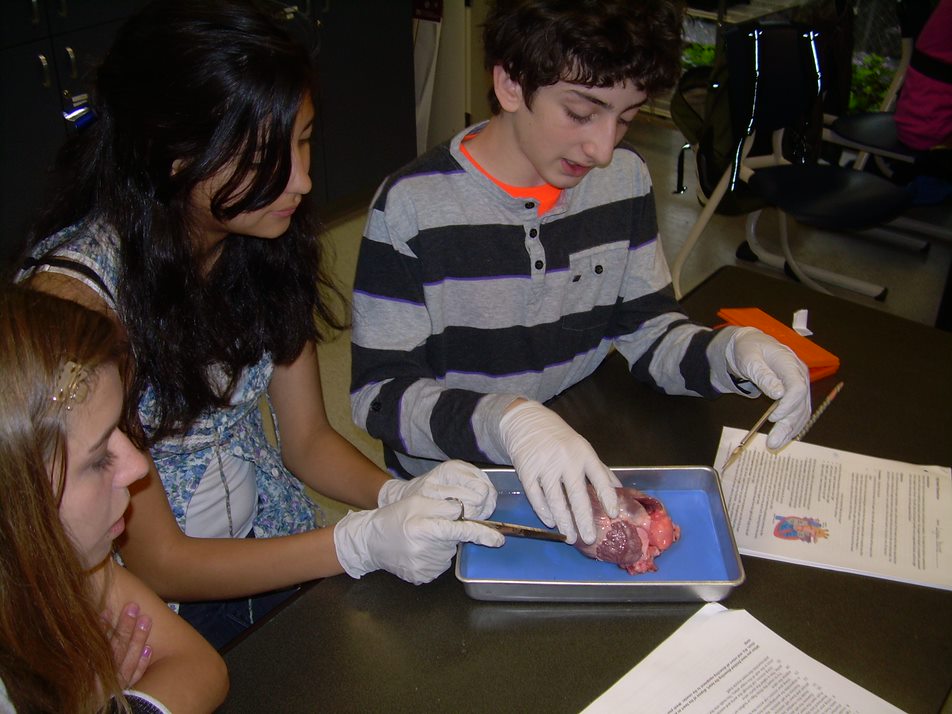

And quite frankly, there are some days when I love having visitors, such as when I invite Sam Uzwack to join us when we’re dissecting pig hearts. I’m not sure that he enjoys it quite as much as I do, though.

(3) seeks out diverse opinions of others for guidance

To me, this is the one of the best parts of working at EPS. I have so much respect for the knowledge and skills of my colleagues and I am very comfortable reaching out to talk through a whole host of concerns. Numerous examples spring to mind. A recurring one is that I connect with Learning Support whenever I am designing a new project.

I have found it immensely helpful over the years to have them read instructions for clarity and to help me with scaffolding larger assignments. This of course helps not only students with accommodations, but also improves the experience for all students.

“From the time I began in Learning Support, Katie has partnered with me and other members of learning support to change, adapt and learn how to make her lessons and projects more accessible to students with various learning challenges.”

–Mike Anderson

When I was assigned the new US Ecology class, I reached out to several US science teachers to gauge my level of challenge and overall course design. Nickie Wallace and I worked together to propose the class in the first place, and although she ultimately did not end up teaching it, I sought her input on a variety of topics related to the class. I can vividly recall talking with her about how she approached test-writing in her US classes, which was a helpful framework for me.

I regularly reach out to Sam to talk through tough situations, such as when we met in October of 2021 to discuss an advisee that I was finding it difficult to connect with. I know that Sam always has great suggestions and never makes me feel bad for having these kinds of struggles.

In fact, I think that so much of it boils down to the fact that EPS feels like a safe space for me to ask questions and display that vulnerability of not always having all of the answers. I’m someone who LIKES KNOWING THE ANSWER and who struggles with uncertainty, and knowing that I’ve got a supportive environment helps me feel that I’m given the space and the permission to grow.

(4) manages and prioritizes professional tasks and responsibilities

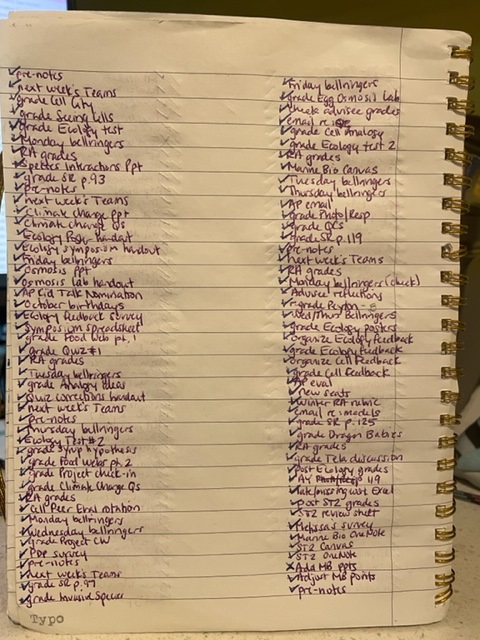

I am someone who loves a to-do list. In fact, I have a notebook in which I keep my to-do lists, and it dates back several school years.

I find it immensely satisfying to cross things off of a list, to the point that I’ve been guilty of adding an already-completed task to my to-do list just so that I can cross it off immediately. Apparently this is a characteristic of the Achiever strength:

My to-do list tends to be focused on the day-to-day tasks such as grading, posting pre-notes, reviewing handouts or PowerPoints, etc.

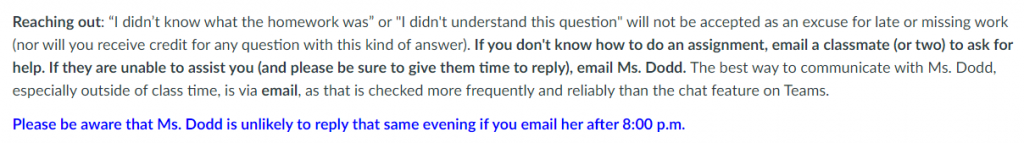

I try to keep the number of messages in my inbox fairly low. I treat it like another to-do list, and will leave relevant messages in the inbox until the time that they apply has passed (such as grade-level advisory plans for a given week). I have established (and stated in my class syllabi) that I don’t respond to emails after 8:00 p.m. I hold true to this for students and parents, but sometimes will respond to emails from colleagues if I see them later in the evening. It’s important to me that I am available via email for a little while after school as I tell students that they should reach out to me with questions.

(5) communicates and responds to students, parents, and colleagues in a timely and constructive manner

As mentioned just above, I have worked to find a balance between responsiveness and maintaining boundaries regarding communication.

Another piece of advice I received early in my time at EPS (from former colleague Cascade Lineback) is to respond to any sort of emotionally charged email from a parent with a phone call. It always feels harder (and quite frankly, a little scarier) to call a parent who is clearly upset, but I have found that this tends to lead to positive outcomes. Tone can be so hard to read via email, and having a back-and-forth that way can compound misunderstandings or allow people to form a potentially incorrect perspective by “reading into” a message, and talking directly on the phone removes many of those barriers. I have yet to regret making a phone call instead of replying to a difficult email.

While I work hard to be responsive to email, over the years I have also recognized that immediate replies are not always the best option, so I am intentional about which messages get a quick response and which might wait until the next day. As mentioned in another section, I also don’t reply to student emails after 8:00 pm (and this is clearly stated in my class syllabi).

Assessment Practice

The indicators below largely focus on my current practices with regard to assessing students. As my assessment practices have changed over the years, I anticipate that these will be more of a snapshot than a roadmap for my classes. In particular, as I move forward I would like to find more opportunities to step back and examine my assessment practices more closely in terms of how they connect to student experiences and how well they reflect true understanding. This is something I’ve been in conversation about with Jamie Andrus, and I look forward to continuing to adapt and develop my practice in future years.

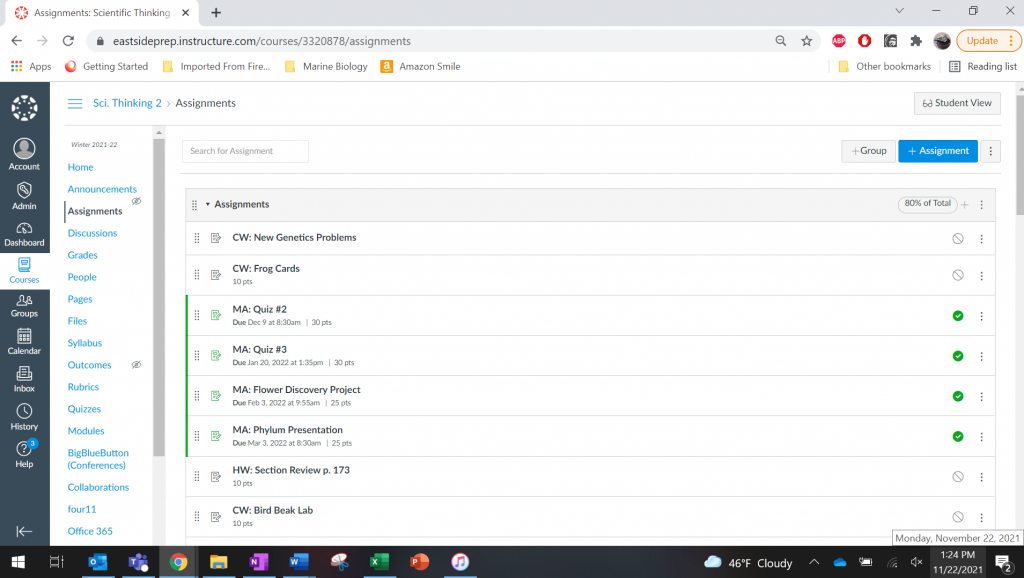

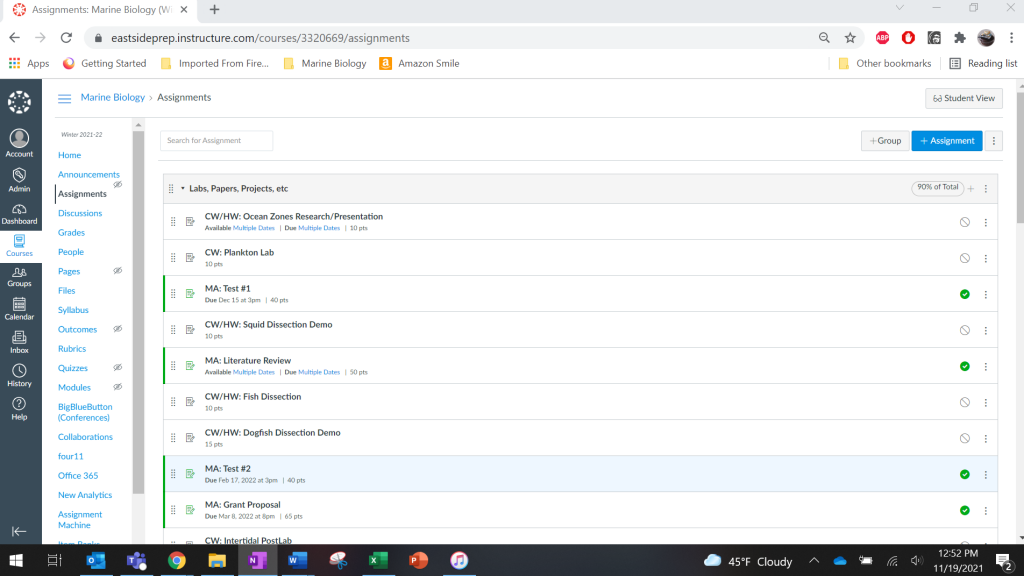

(1) designs major assessments that reflect course outcomes and posts them at the start of each trimester

Since this is a stated expectation, I am diligent about having my MAs posted before I publish my Canvas pages for each class.

I try to have several different types of assessments in my 7th grade Scientific Thinking 2 class. These include lab write-ups, quizzes, projects and presentations. The hope is that by providing different ways of showing their knowledge this can help students both work with assessments that are perhaps more familiar or preferable to them while also giving them an opportunity to stretch by exposing them to other ways of showing their knowledge.

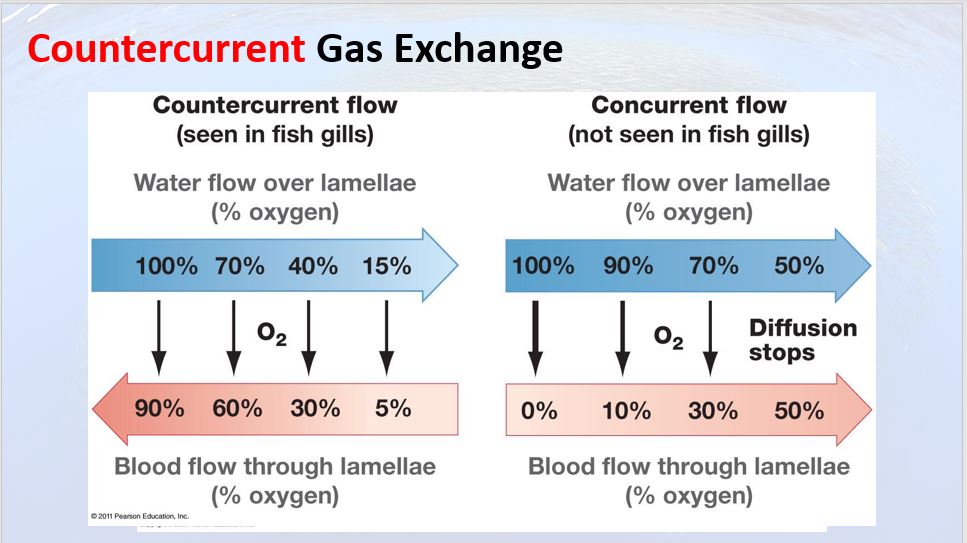

When designing the new Upper School electives of Ecology and Marine Biology, I was intentional about the types of assessments I wanted students to experience to differentiate these classes from their other high school courses and also to give them a preview of the types of assessments they might experience in college-level organismal biology classes. On tests, I wanted to challenge them with higher-level-thinking questions (for example, where they were asked to apply concepts and recognize them in real-world contexts). Many students have reported that the tests were tougher than they initially anticipated, but that they enjoyed facing these different questions (well, as much as anyone can “enjoy” such a thing).

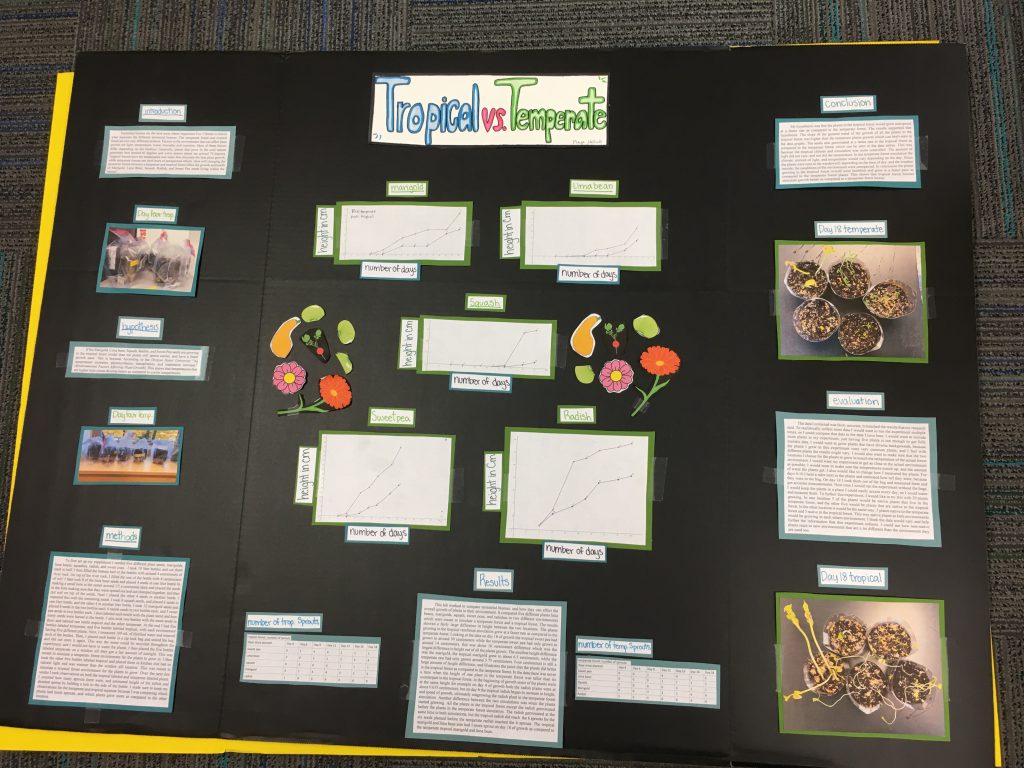

I also wanted to differentiate between the types of assessments in Ecology vs. Marine Biology. To that end, for Ecology the most significant assessment is a long-running (e.g., approximately one-month) experiment that is entirely student designed, where they (working alone or in pairs) design a study that examines the impact of an abiotic manipulated variable on a biotic responding variable. They must then participate in a symposium where they present their research (using a scientific-conference-style poster) to their classmates.

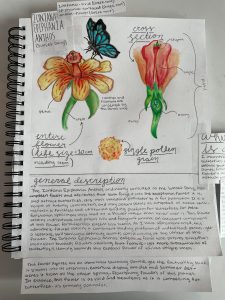

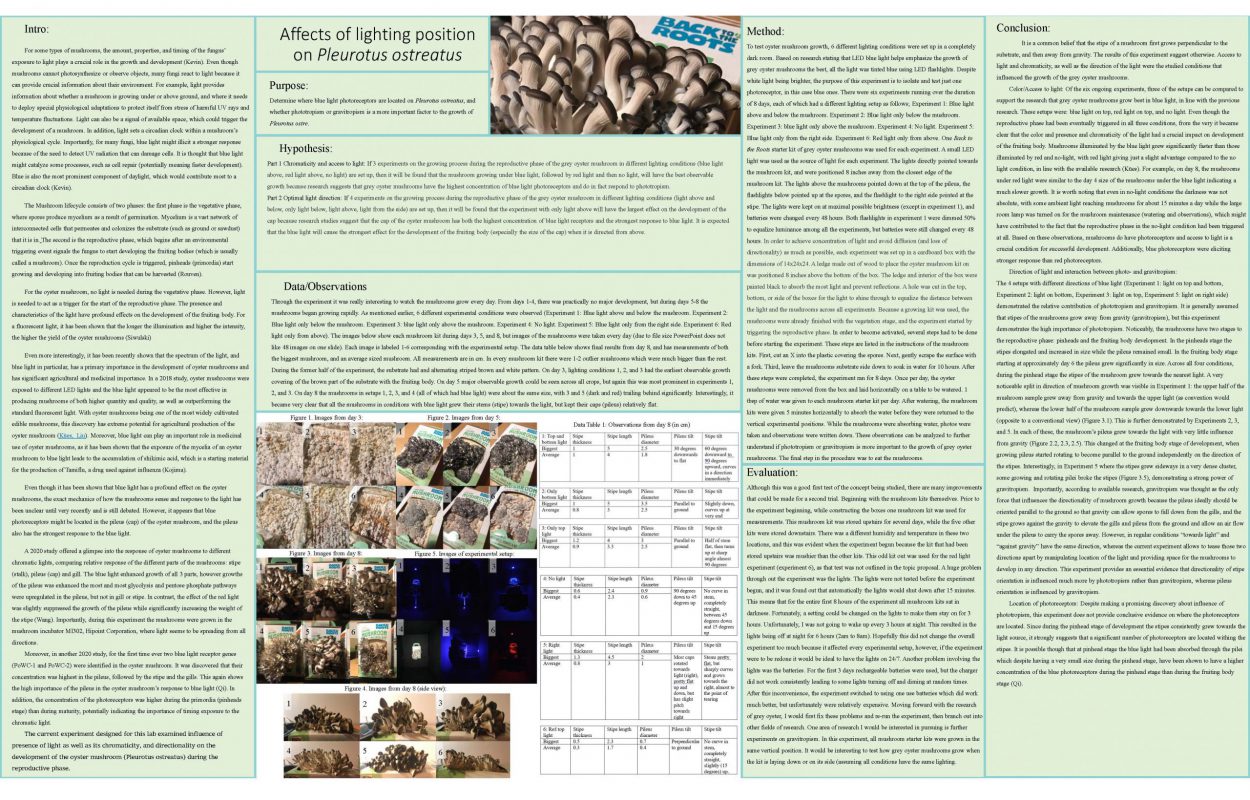

In Marine Biology, I chose to focus on research and writing skills. Students pick a marine species of their choosing and then write two papers. The first is a literature review–a summary of current knowledge about their species. This paper requires students to dive (ha ha) into scientific literature, using sources such as Google Scholar and JSTOR to find peer-reviewed studies. They are also practicing their scientific writing, which is not always something that’s emphasized in high school classes. Once they have learned what is known about their species, the second paper they write (which is the final for the class) is a grant proposal for a study that would allow them to try to answer one of the unknowns for their organism. This includes not only planning a detailed study but also researching and creating a budget. Students read and evaluate one another’s proposals and ultimately decide to allocate funding based on their appraisal of the proposals.

(2) designs assignments to be graded and returned in a feedback cycle of seven calendar days

When students are submitting any sort of MA, I’m very clear that it’s going to take time for me to evaluate and assess their work. Even on the rare occasion that I might be able to complete my grading by the next class period, I don’t return work at that time as I think that’s not a reasonable expectation to instill in them. I would say that in many cases I attempt to return larger work by the second class period after the one in which they submit it, although this is easier to do with tests than with larger projects. I have not experienced complaints from students as far as the turnaround in my grading is concerned–if anything, they sometimes express surprise at how quickly I have been able to return graded work to them.

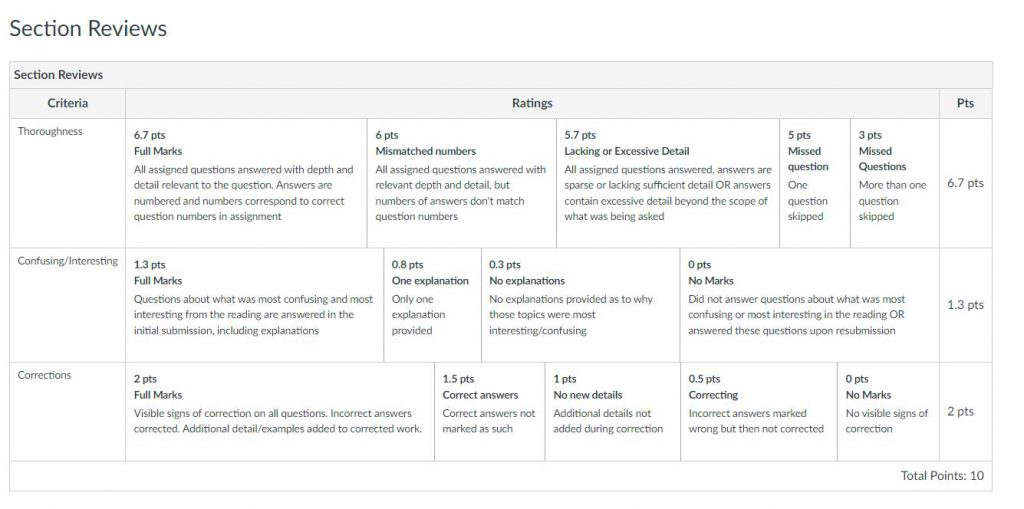

Over the years I have streamlined the amount of feedback given. With a few exceptions, most classwork and homework assignments are graded by the next class period. For recurring assignments such as the section reviews that my seventh graders complete, I have a rubric that easily allows me to grade their submissions. The same is true for their weekly responsible action grade.

An area with some room for improvement is intentionally giving time in class for kids to read feedback given, particularly feedback that lives only on Canvas.

(3) ensures the number of assignments in each course is neither excessive nor deficient — providing appropriate time for quality student performance and meaningful teacher feedback

My aim, particularly for my seventh grade class, is to give students enough small assignments that there is some forgiveness in the grade book for lapses in work over the course of the trimester. In the past, I had a separate grading category for major assessments but found that this gave those assignments an outsized influence on the overall class grade early in the trimester, which in turn caused undue stress for students. By including all work in one category (with Responsible Action separated out as 20% of the grade), students get more of a real-time sense of how they’re doing instead of having to wait for a large assignment to drop to see a big impact on their grade.

For my Upper School classes, this is a bit flipped. There is very little credit given for most homework and classwork assignments. The MAs and some labs are what make up the bulk of the grade. Again, this is done intentionally to try to mimic the weight that assignments may have in college courses.

As far as frequency of MAs is concerned, I typically aim for three per trimester.