These categories and indicators can help to paint a picture of what students are experiencing in my classes on an ongoing basis. A common thread that runs through this domain for me is the idea of having high standards communicated in a caring way. This looks a little different in Middle School vs. Upper School, connected to the different developmental stages (and needs) of these two groups of students.

Classroom Culture

The culture in the classroom is absolutely essential to student success, and requires intentionality in its planning as well as regular maintenance. I appreciate that we can point to our school mission statement to help reinforce expectations. This also provides some consistency as students move through their day–although my expectations may not be exactly the same as those of another teacher, they are in service of the same overall school culture.

(1) coaches and reinforces peer-to-peer dynamics that are appropriate and constructive

I think that when a lot of people think about their own Middle School experiences, it’s the peer dynamics that spring to mind far more often than anything they learned in the classroom. And for many people, these memories aren’t positive ones.

One of my goals in working with students in our Middle School is to help them develop some of the interpersonal skills necessary to navigate the world in a positive way. A big part of that is modeling behaviors for them and in some cases explicitly teaching them things or offering them “scripts” that they can use with one another. I know this is a continuation of much of the work that’s done with them by their 5th and 6th grade teachers and advisors, and I think these so-called “soft skills” are an incredibly important part of what they acquire during their middle school years.

For example, when a new seating chart is posted, I discuss their reactions, saying, “Whether you are excited to be seated with a friend, or excited for an opportunity to build a new connection” (framing it as a positive no matter what).

Similarly, before students are partnered (whether that’s intentionally or randomly, using the “Sticks of Choosing”) I remind them that their reaction to the pairing can impact the success of the partnership, pointing out that exclaiming “Oh, ew!” would likely make someone not too excited to work with them. I also say to the students, “Remember, this partnership is not a lifetime commitment.” I then inject a little humor into the moment by adding, “Of course, if it does lead to one, please be sure to invite me to your commitment ceremony!” For years this elicited the expected groans and eye rolls, until one amazing year when a 7th grade student told me that her parents met as lab partners. Vindication!

Similarly, when I return graded assignments, particularly major assessments, I remind the students that their grade is their business and no one else’s. I point out that while they may be happy about their grade and eager to share, their neighbor may not be having the same experience. I provide a sample script of what they can say to one another, and this was actually witnessed and noted by one of my team members during a class observation:

During the last few minutes of class, you asked students to, “find your way back to your seat,” as you distributed results of a quiz. As you did so, you reminded students that they have the power not to share their grade with other students by saying, “Remember you can say, ‘Gentle neighbor, I have nothing but the utmost respect for you, but my grade is my own business.”

–Randy Reina, class observation February, 2022

(2) communicates behavioral expectations that are appropriate to class activities

Just as I make a point of explicitly teaching them some interpersonal skills, I think it’s incredibly important to be clear and consistent in terms of classroom expectations. At the start of the year in 7th grade, the students work together on a “Syllabus Scavenger Hunt” that requires them to find key pieces of information on the class syllabus on Canvas. There is also a handout that has more specifics about Responsible Action, which lays out many examples to help clarify my expectations of them. In addition, each day when they enter the classroom, there is a bellringer on the board which provides instruction for how class will begin.

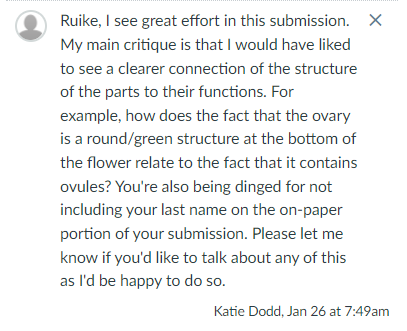

Students receive a weekly responsible action grade, and there is a rubric for this assignment. I indicate the importance of this in my Middle School classes by allocating 20% of the overall grade to this category. I also offer specific feedback in those instances where students lose credit from this grade. For example, “[Name removed], please remember that I have very specific expectations for following up on an absence. I’m happy to talk more about those with you if you aren’t certain of them–please just let me know! Thanks.” Another example of a comment is,”[Name removed], I don’t think I saw your hand during our HW review on Wednesday? Please let me know what I can do to help support you if sharing answers is feeling challenging sometimes! You’re also being docked a little credit as you needed to charge your computer that day.” Because these are laid out pretty clearly, I seldom get pushback from students if they lose points in a given week (although emails seeking clarification do come in from time to time).

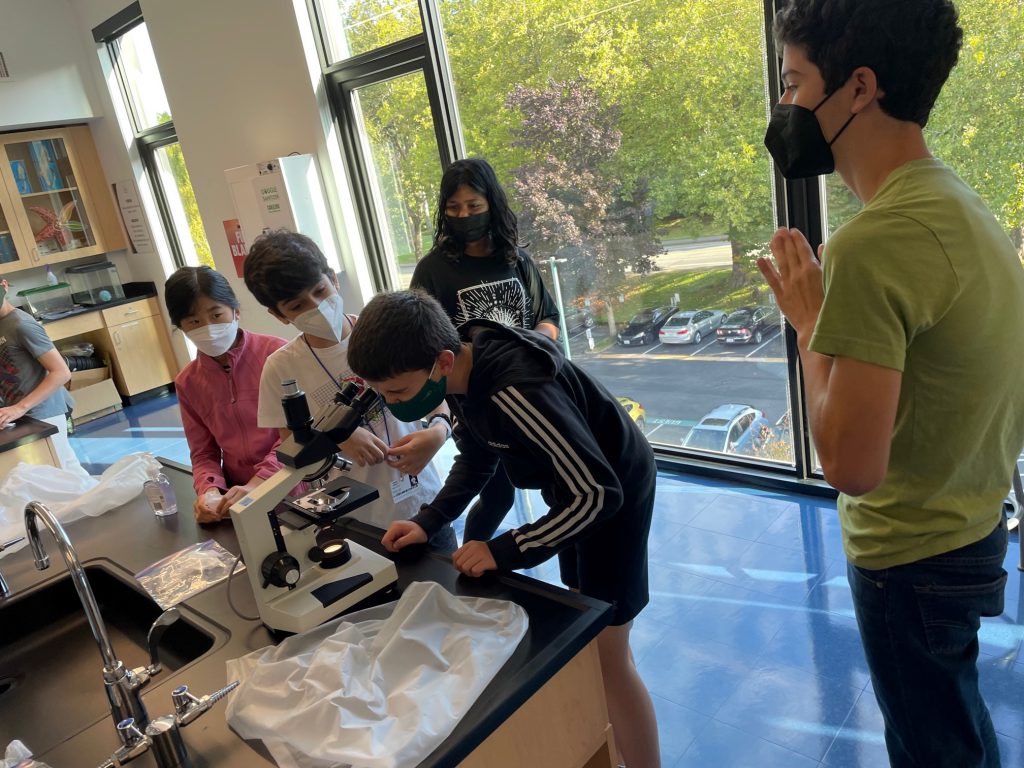

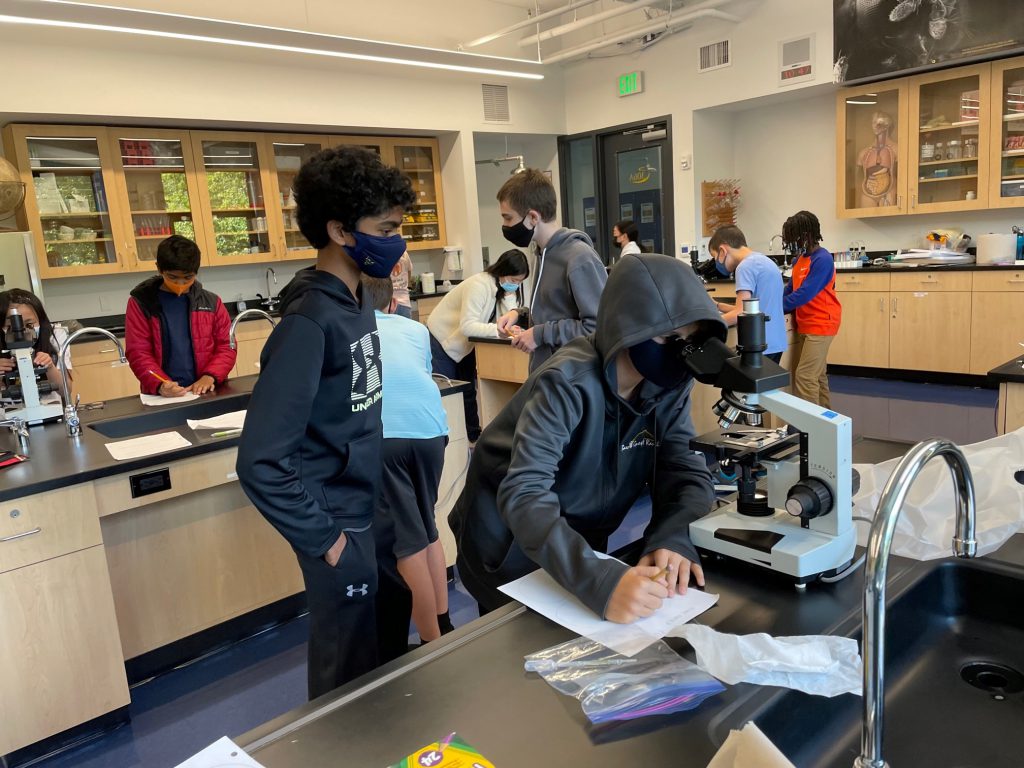

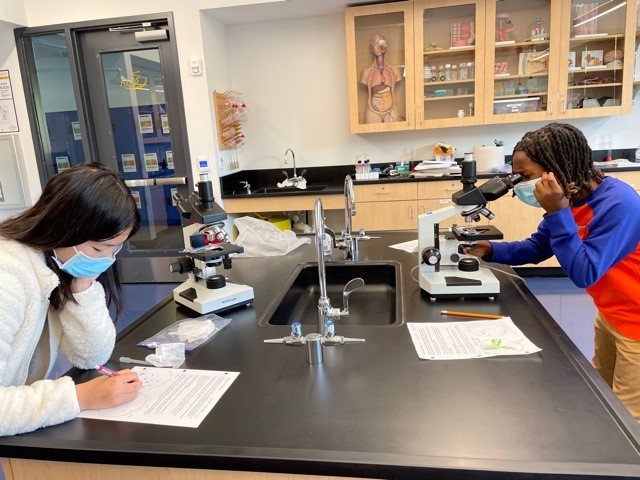

As far as how to properly use classroom tools, this is also something that is folded into the instruction. The most complicated device we use in 7th grade Science is the microscope, so we spend a fair amount of time learning how to operate it properly. Students have several assignments where they learn the names and functions of the different microscope parts before we use them in a more scientific fashion. When accidents occur and/or equipment gets broken, the conversation with students is focused from a safety and learning perspective (e.g., asking first if they’re okay, and then reflecting on what happened and why) rather than a disciplinary approach. I have found that these approaches allow students to be successful with even somewhat delicate equipment.

In all interactions with students, I seek to be equitable and consistent in terms of communication. All in all, I hope that my clear expectations provide some stability and predictability as to what will happen in the classroom. While I know some students would prefer a looser approach, there are many who find the predictability calming. On top of that, having clearly communicated expectations also helps keep students safe in a lab setting.

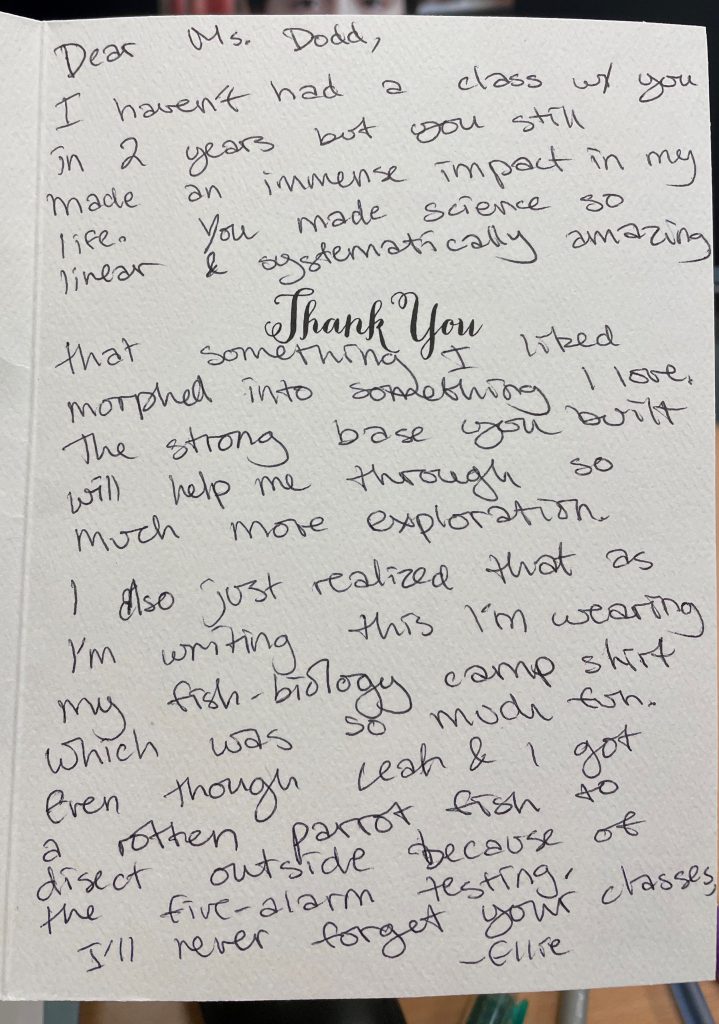

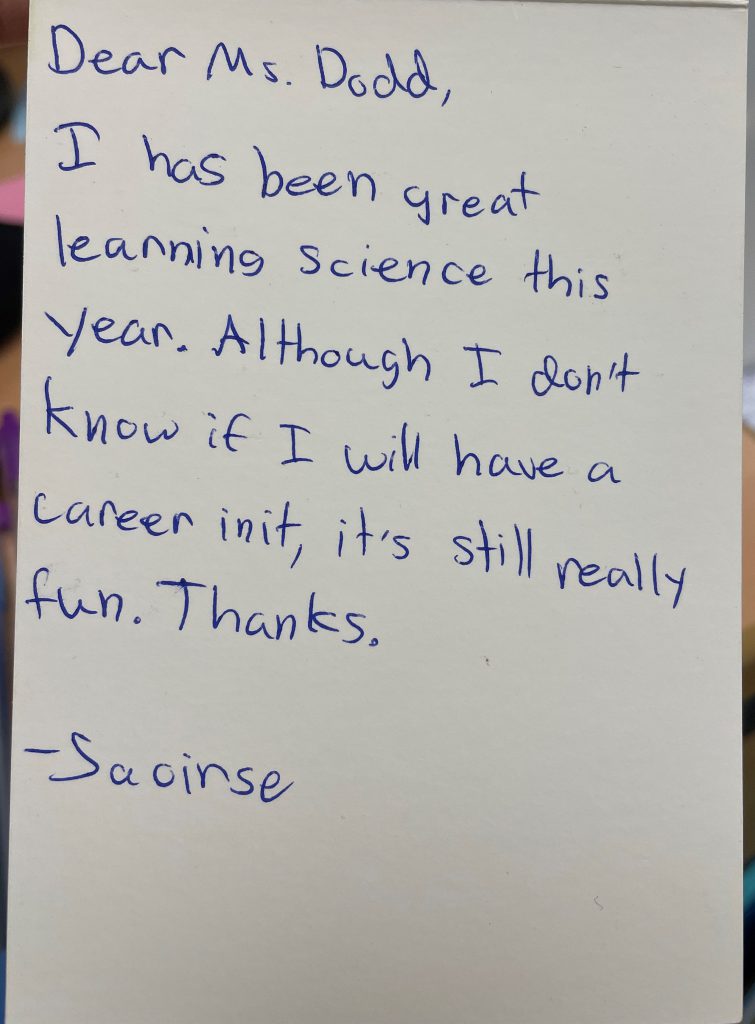

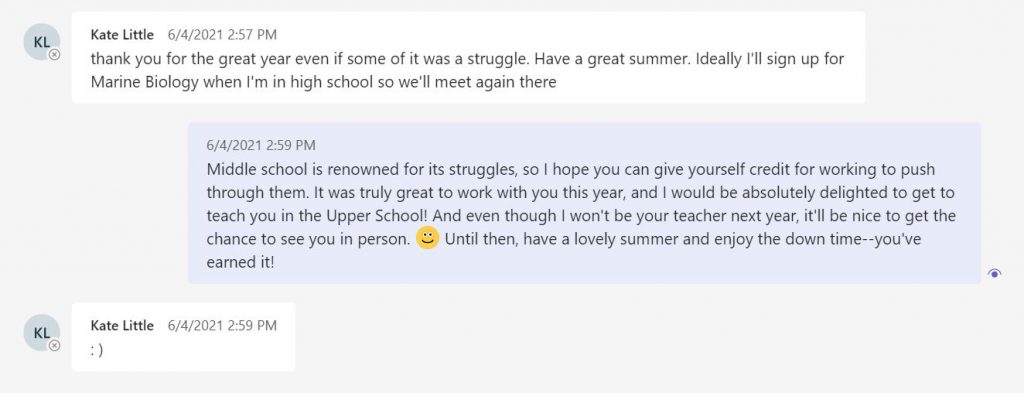

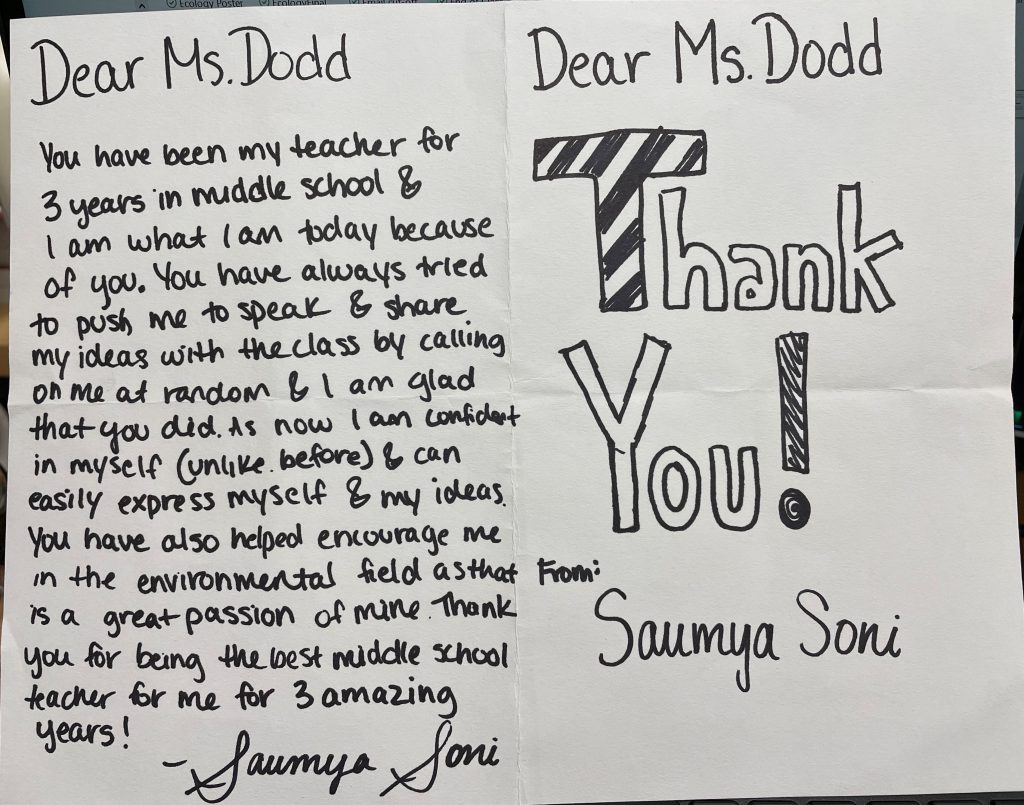

(3) develops a mutually respectful relationship with each student, instilling confidence that the teacher is invested in their success

This is an incredibly important indicator to me, but it’s also one that I think is a little challenging to assess. My goal is to be perceived in essence as a “warm demander,” where I hold the students to high expectations but also work to help them get there.

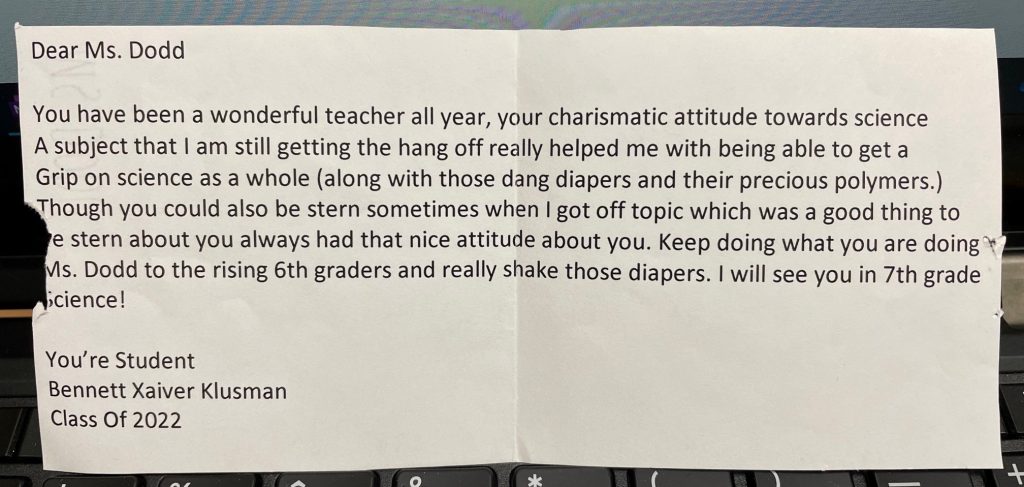

My greatest goal as a Middle School science teacher is to help students see themselves as successful scientists, and (ideally) to help foster or develop an interest in some aspect of science.

This is one of the reasons that I require students to meet with me if they earn a D or an F on a quiz. I want to talk to them about the quiz, and about their preparation as well as their test-taking strategies. Most of the time when a student doesn’t do well on a quiz, there are challenges in one of these areas. My goal in having the conversation is to normalize the struggle and to remind them that it’s okay not to have all of this figured out yet–that middle school is the time to be trying out new study strategies. In having conversations about these strategies, and offering specific suggestions, I hope that I am encouraging the students and reminding them that they are a “work in progress” (as are we all).

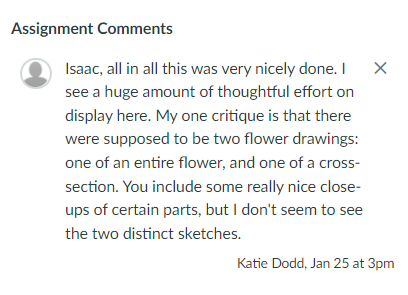

I’m also mindful of the way tone may be perceived in all of the written feedback I give, from small assignments on Canvas to mid-trimester progress reports. I always provide some sort of detail if points are lost on an assignment, and I try to start any critical feedback on Canvas with a positive statement of something that was done well.

Again, I want to encourage and reward the effort, as that’s so much of what I’m hoping to see from students. In recent years I’ve also been mindful of not praising answers based just on “detail,” as there are many students who have a tendency to overwork. Instead, I discuss “relevant” detail, trying to emphasize the quality of the work over the quantity, and also encourage some students to put less time and effort into their assignments (especially low point-value ones).

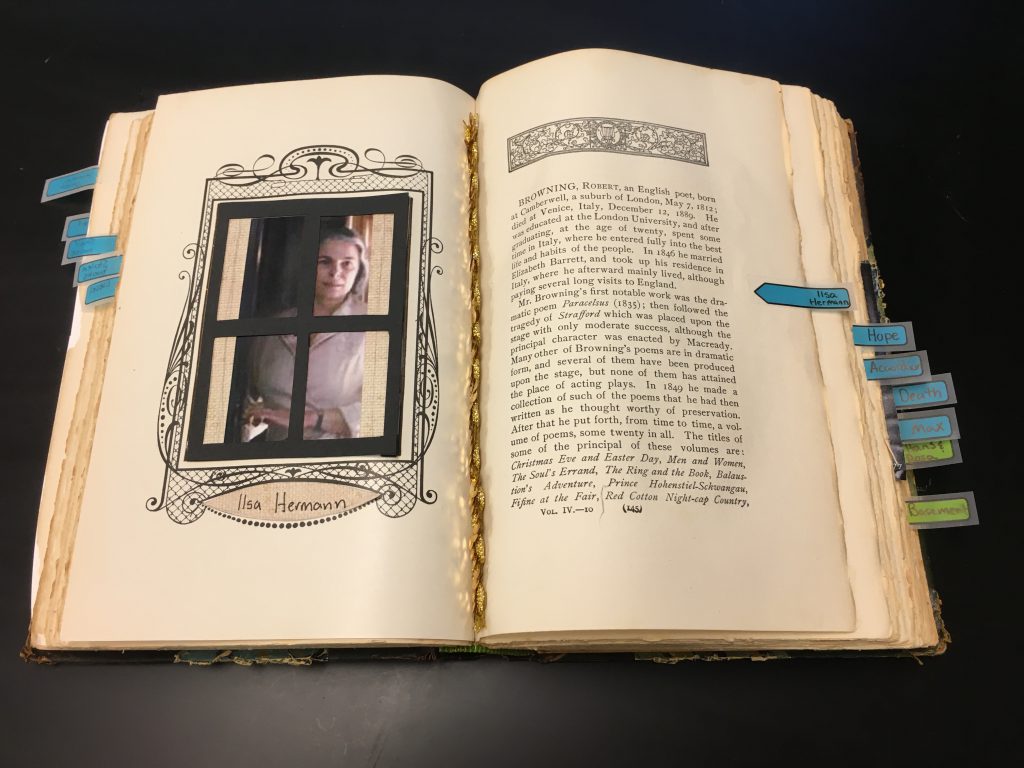

I invest a great deal of time and care into the mid-trimester comments that I write. For each of these, I work to bring the students’ voices in by asking them to answer a few questions about their science class. This helps those comments feel personalized and hopefully help the students feel that I am invested in their progress and am rooting for their success.

For those who are really struggling, I seek to be encouraging and also supportive, reminding them that they’re not expected to “go it alone”–I’m here to help them on this journey.

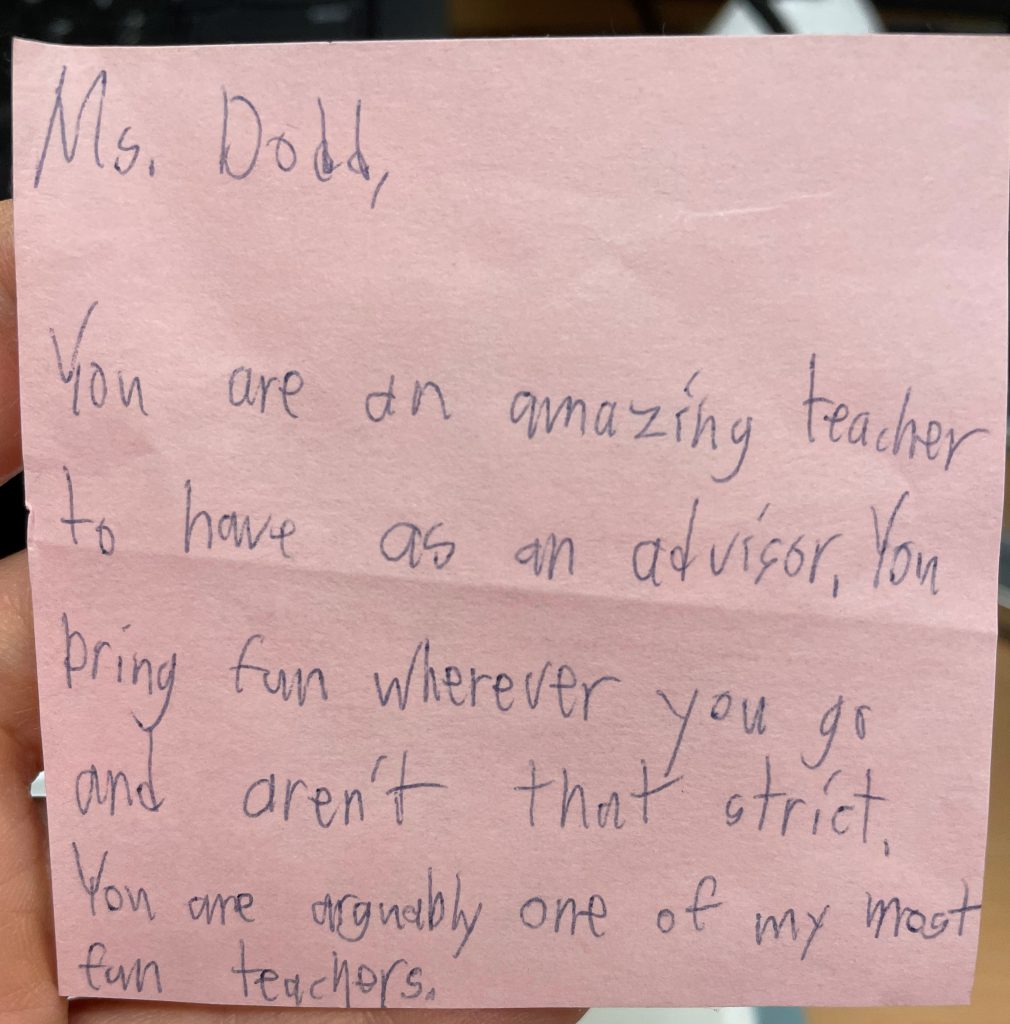

I also seek to normalize some of the challenges that many of them experience during Middle School, such as handling a larger work load or developing new study strategies. This “long view” is also helpful in my role as an advisor. I have learned over the years through numerous conversations with Sam Uzwack that I can’t support a student to the best of my ability if I haven’t invested the time to build a mutually respectful relationship with that student. Giving myself permission to spend some time on that relationship-building has helped me be a better advisor.

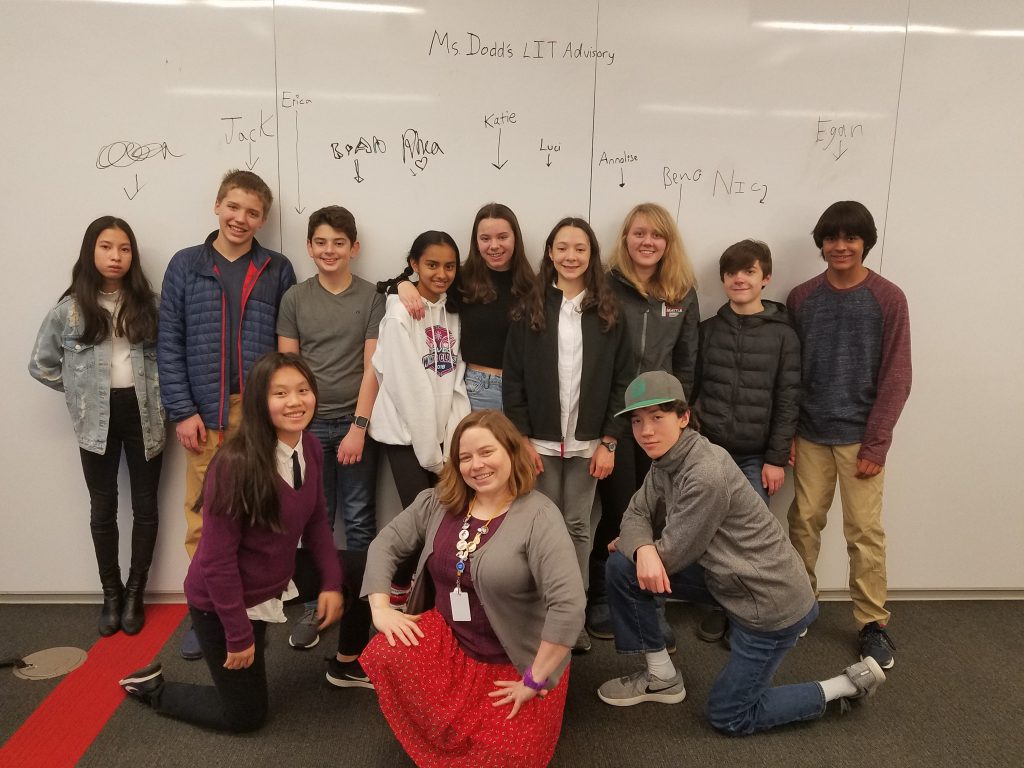

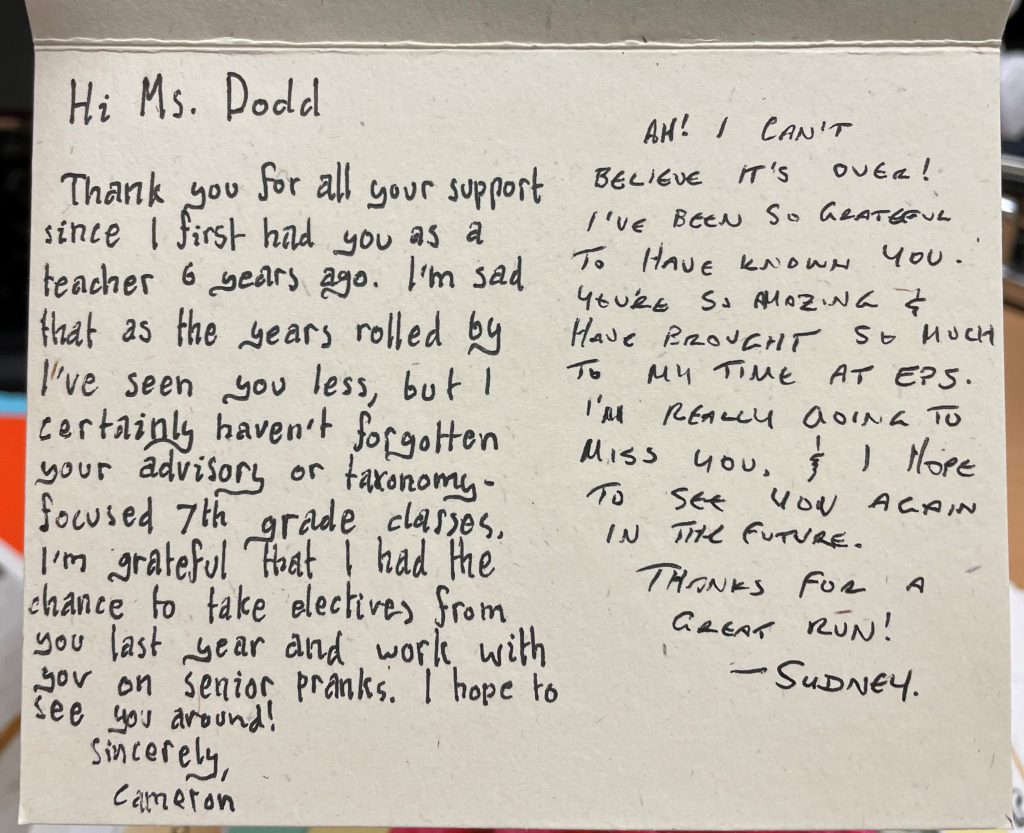

My relationship with Erica Newell to me is my “gold standard” for this kind of connection, and our interactions have been so rewarding to me over the years. We first worked together when she joined the MS volleyball team in 5th grade.

In her sixth grade year I was her ST1 teacher and again, her volleyball coach.

In 7th and 8th grade I served as her advisor (and continued to teach her). I was one of the chaperones on her 8th grade EBC trip to Santa Fe and gave her speech at Continuation.

Despite not getting to work closely with Erica for the next couple of years, our connection remained strong, through her efforts as well as mine.

And then in her senior spring, Erica enrolled in Marine Biology, and gave me a very sweet shout-out in her senior spotlight.

Of course, not every relationship can achieve this level of connection, but I can’t overemphasize how important and rewarding this has been for me over the years.

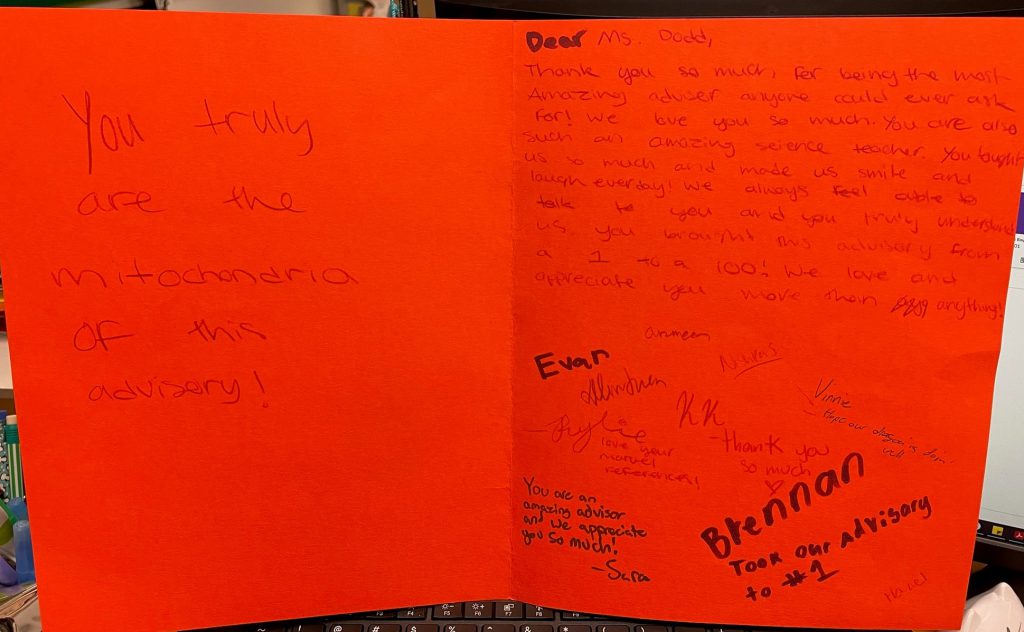

Sometimes I get to know the students in the simultaneous role of science teacher and advisor, as was the case with my past two advisories.

On other occasions I have stepped in and advised a group that I’ve taught previously, building upon positive relationships started in the classroom.

It’s been gratifying that students have usually responded to this sort of situation positively as I think that helps show the atmosphere of trust and support that they experienced in the science classroom.

One thing that’s been particularly lovely about getting to teach certain students again in Upper School is to see the growth that they experience over the years–it’s a nice reminder that for many students it’s important to have the long view, and that many of the changes we hope our students experience take place over years, not months.

The work done with the students in the Middle School is developing the foundation that they will continue to build upon as they progress to our Upper School. Getting to write a college recommendation for a former advisee and to discuss them over the years is incredibly rewarding.

(4) demonstrates cultural competence by promoting inclusivity

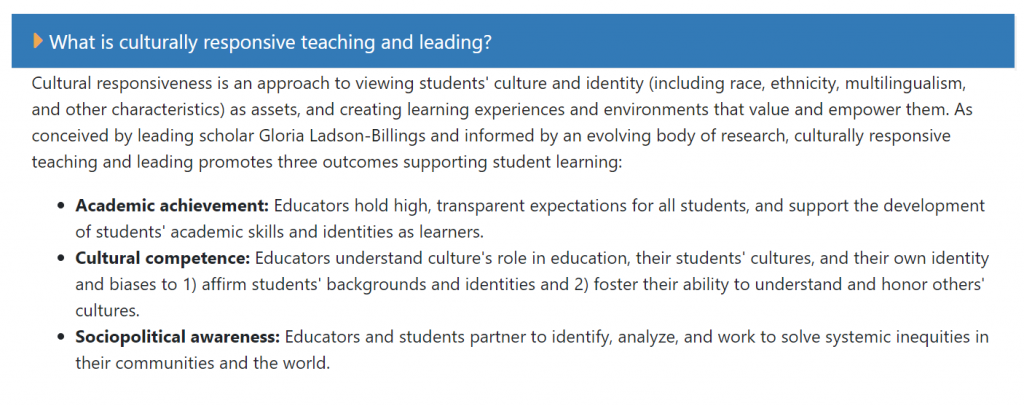

The first challenge I see in this indicator is defining what “cultural competence” means to me, as this is a term that doesn’t yet have a shared definition here at EPS. I found a helpful document created by the University of Delaware that defines many of these terms and offers some specifics in terms of justification as well as strategies. As I currently understand this term, it’s about increasing my knowledge of my students’ backgrounds to become aware of the gaps in that knowledge as well as biases that I may be bringing into the classroom as a result of my own background and upbringing. This connects to the specifics of what is often termed “culturally responsive teaching.” I found clarification on this in the Massachusetts Department of Education website.

I think that I am fairly strong in the first area. As I have referenced elsewhere in this portfolio, I work to clearly communicate my expectations to students and root for all of them to succeed.

I also frequently offer my support to students as I view their progress as a partnership, and my role is to help them discover and develop their strengths.

While I’ve done work on the second metric, this is an area that I think has room for improvement. I have made small adjustments over the years, such as using gender-neutral language on handouts and in the classroom, and making sure that even any cartoony drawings of scientists used on handouts include people of color. I have more details about some of the work I’ve done here in the Relational Cultivation indicator connecting to recognizing and supporting diversity, so I won’t repeat those points here but will instead direct the reader there for more examples and discussion.

I do believe that I would benefit from learning more about the different cultural backgrounds of my students–for example, I am not very familiar with various Indian holidays and traditions but know they are practiced by many families in our community (and that “Indian” is a term that encompasses many different cultures and faiths, so even in using this term I am oversimplifying).

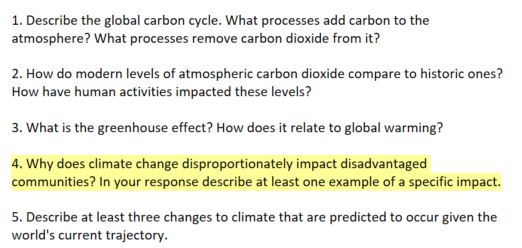

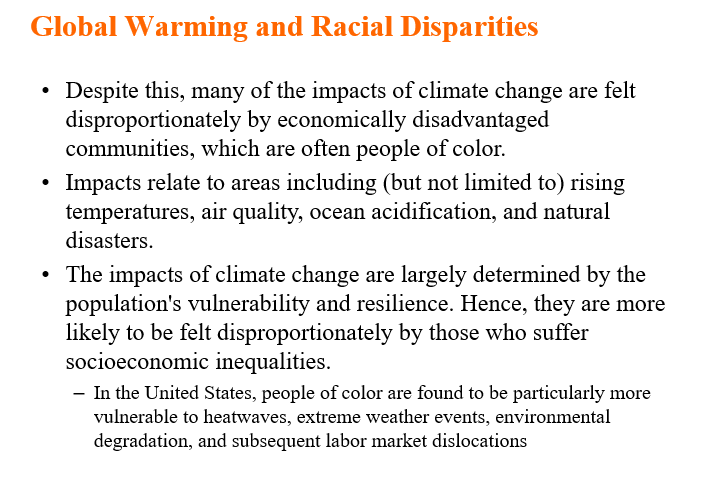

As far as the third point is concerned, this is not something that has been a specific area of focus in most classes. We address it briefly in Ecology in the context of climate change.

It comes up more often in conversations/discussions in classes. For example, in 7th grade this year a student asked if there was ever selective breeding in humans, which led to a brief discussion on slavery and people not having freedom over their own reproductive choices, but this arose through happenstance and isn’t part of the regular curriculum. I believe that there are likely more opportunities to thread this kind of connection through the broader class, but have struggled a bit with how to do so.

What I particularly struggle with is a way to do this kind of work authentically and that doesn’t feel like tokenism, especially given the fact that I am white. In fact, this is my EICL goal for the 21-22 school year. One piece that feels challenging to me is a way to gather authentic feedback from students about how well they feel seen and known in my classroom. I need to talk more with Bess and Ed (our EICL Coordinators) about how to best start this process. I spent time over the winter break exploring the website of The Underrepresentation Curriculum Project, which, per its website is “A flexible curriculum designed to help students critically examine scientific fields and take action for equity, inclusion and justice.” What I found on this website was thought-provoking, but much of it felt too sophisticated for MS students to tackle. I also hadn’t realized that it was an actual curriculum to teach, rather than suggestions/guidelines of how to incorporate these kinds of principles into one’s own teaching practice.

(5) designs and facilitates a classroom culture that promotes student preparedness, engagement, self-advocacy, perseverance, and collaboration

Some of this I feel like I’ve discussed in other sections, such as how to frame things for students when they are working together. So much of Middle School is about trying new things, taking risks, and picking oneself up and moving forward in those times when we stumble, and I try to frame much of my class this way while still holding students accountable to expectations.

Some of these (preparedness, engagement) are metrics that I address in my Responsible Action rubric. By drawing a clear line between expectation and outcome, there is consistency and hopefully a sense of fairness to students.

As mentioned previously, I’m very mindful of my tone in terms of the feedback I give to students on assignments in Canvas. I try to always have something positive to say before I comment on something that was missing or incorrect, as I don’t want to be discouraging. I do the same thing in class, reminding students that there are no stupid questions, and taking their questions seriously, even when they are a bit off topic. As part of this, I have grown more comfortable admitting when I don’t know the answer to a student’s question and encouraging someone in the class to look it up (in the moment, if it’s a quick question), or to share further information with me (if it’s something more complex).

Students are given review sheets for quizzes approximately a week in advance of the quiz, and then are given numerous opportunities to ask questions in the classes leading up the assessment. I also intentionally use the phrase, “What questions do you have about the quiz” vs. “Does anyone have any questions about the quiz” to subtly show that I expect and welcome questions. I also discuss some different study strategies with them in advance of their first assessment. In these ways, students are given a lot of support in terms of how to prepare for quizzes.

Of course, that doesn’t always mean that quizzes go the way students hope they will. For that reason I do offer corrections on quizzes (and require them for students scoring below 70%). I’ve talked a little bit in other sections about those quiz correction meetings, but again the idea is that there are some opportunities to make up points lost (although students are always better served by doing well on the quiz the first time around, as corrections can only earn back half the points that were lost).

As far as the self-advocacy piece is concerned, I am very responsive to student emails. I repeatedly remind students that I won’t discuss their individual grades with them during class time, but that I am always happy to set up a time to meet with them and talk further about assignments or grades. I also encourage parents to let their students develop those self-advocacy skills (see example here).

Pedagogical Effectiveness

Over the years I have found that having predictable routines and clearly communicated expectations helps set up my classroom as a place where students feel confident that they know what to do (or they know where to look for that information when they’re not sure). There’s definitely a time investment required to onboard students to these processes, but I find the payoff to be well worth it.

(1) begins class sessions with a clear statement about the lesson’s objectives and place in the progression of course

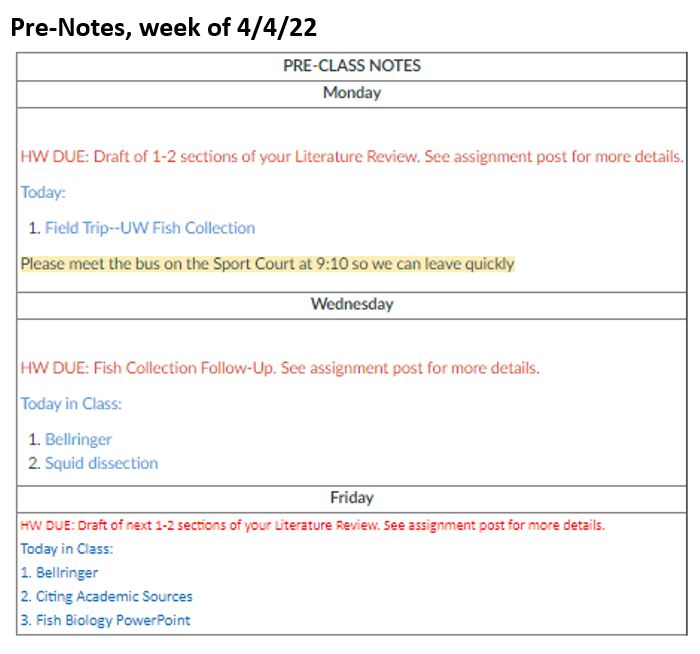

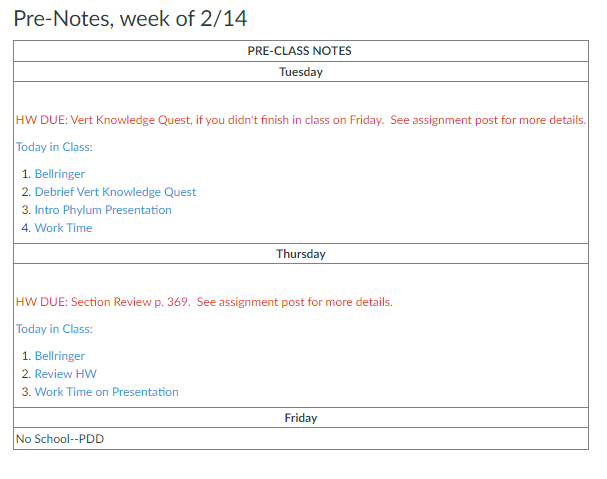

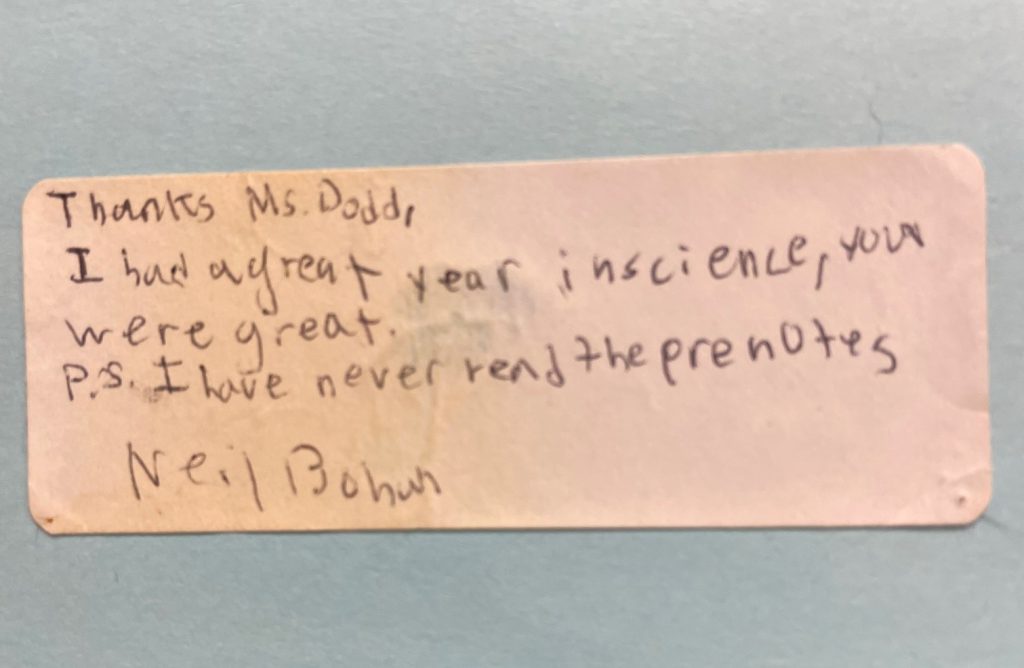

While I don’t typically do this orally, there are many ways in which I convey information about what’s going to happen in class each day. I post pre-notes for my classes.

I was surprised to hear from an Upper Schooler recently that they haven’t had pre-notes for any of their classes for years, although I’m sure their teachers convey agenda information to their classes in other ways (perhaps through shared OneNotes?). I find the pre-notes to be a helpful organizational tool for me, and they also provide students a predictable place where they can find information about a class (particularly useful if they are absent).

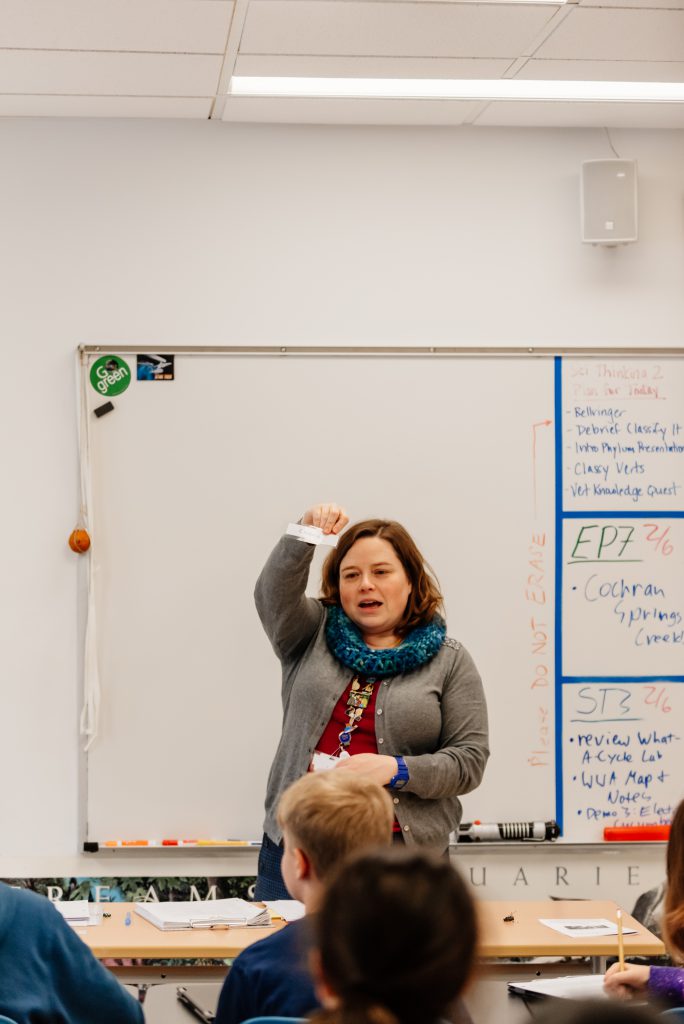

In the MS classroom, I have the day’s agenda (which is typically the same as what was found in the pre-notes) written on the board every day, and it stays up for the duration of the class, which helps students anticipate what’s to come.

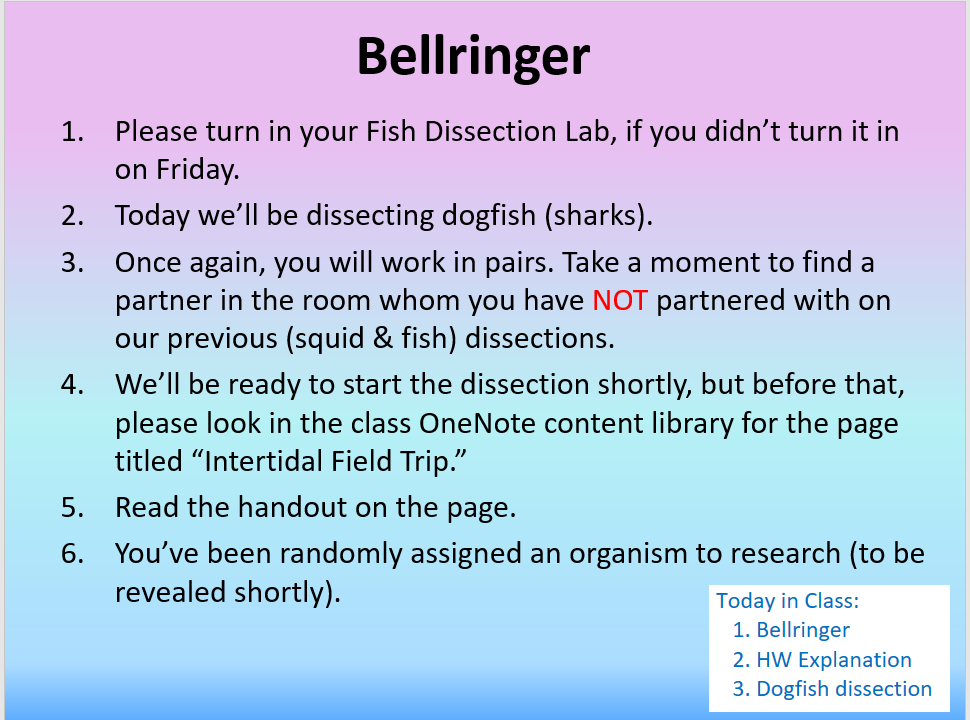

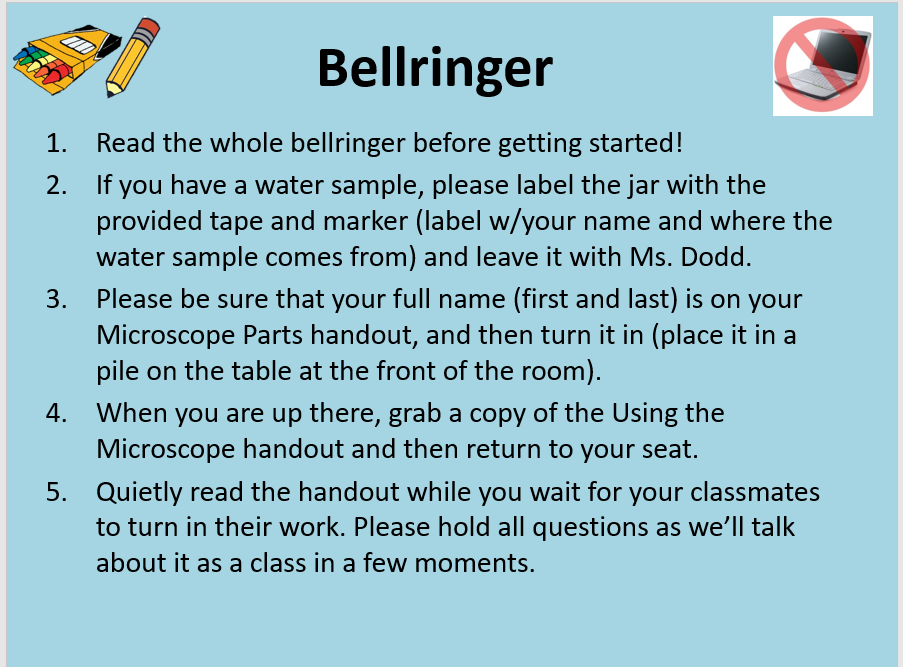

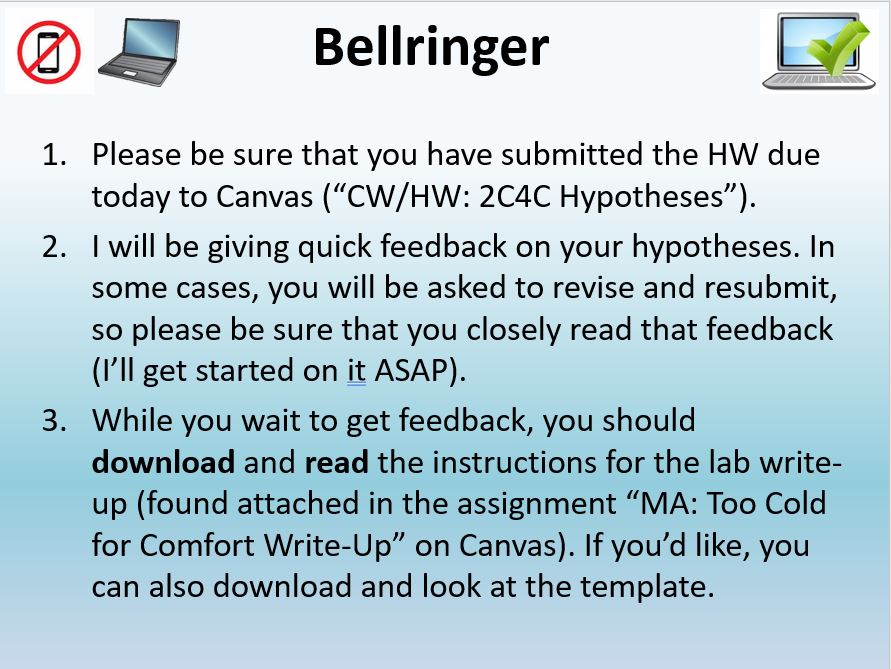

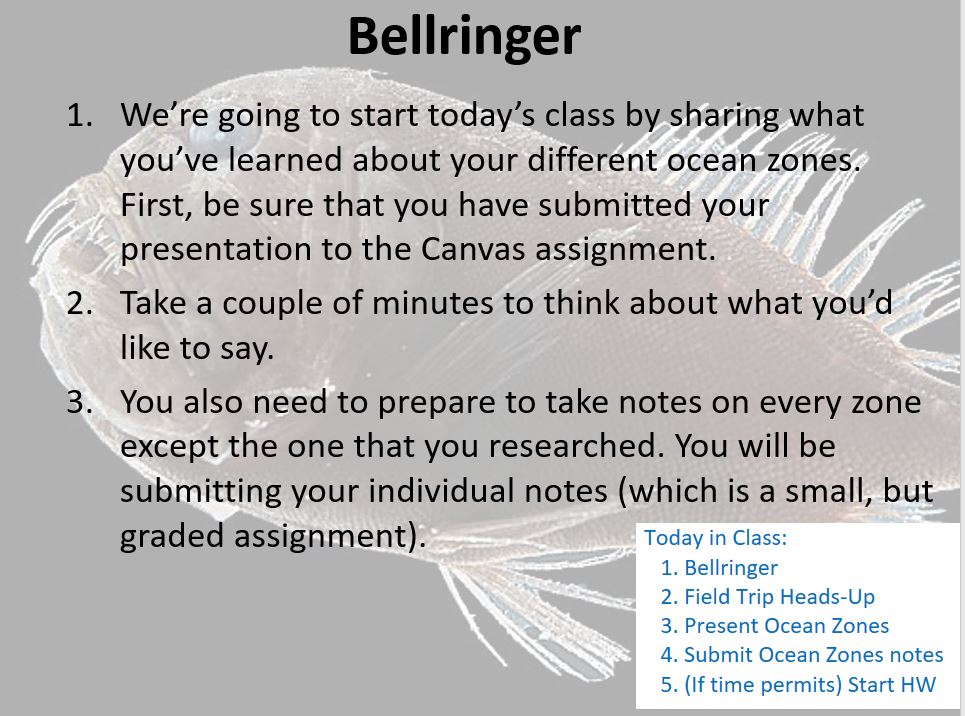

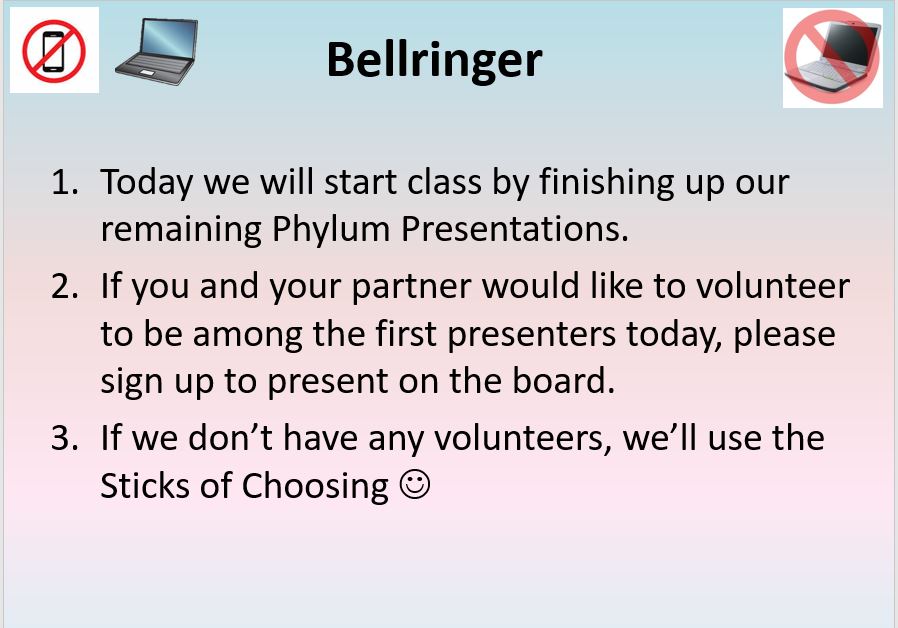

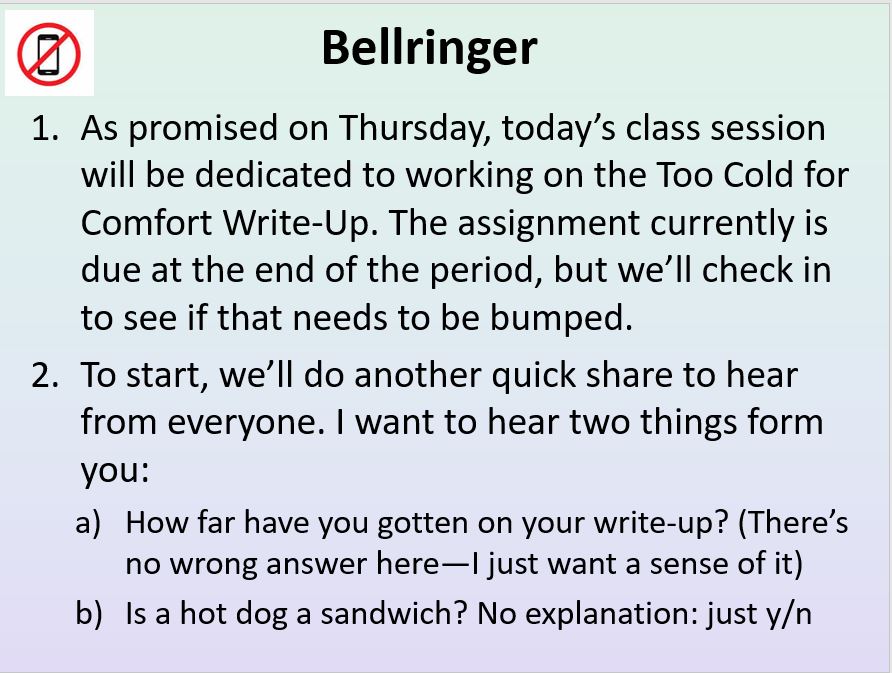

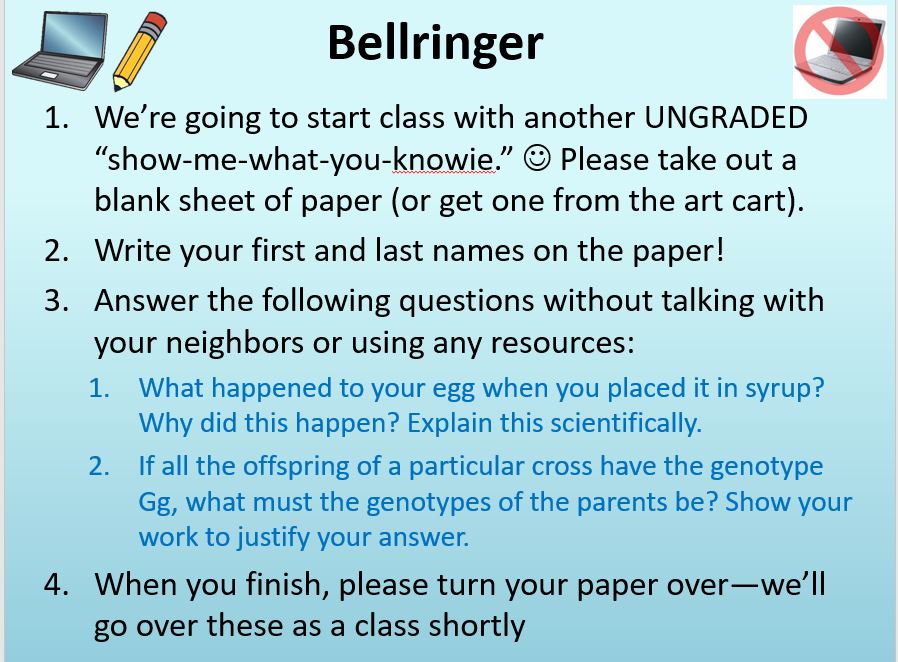

When students enter the room and ask me what we’re doing in class today, my typical response is, “Where can you find that information?” and then they look to the board. In my US classes, I don’t write it on the board but I do include it on the bellringer that is up at the start of each class (see right image, below).

These bellringers are just PowerPoint slides with some instructions for students to follow to prepare themselves to start class.

It will typically have reminders about any HW that was due as well as next steps to help us start class efficiently and effectively. For my 7th grade class (on the left above) I include two sets of icons on each bellringer. On the right-hand sign is an image that tells them whether or not they need the computer to accomplish the bellringer. If they see a “no computer” sign, that means that their laptop should stay closed as they wait for class to start. On the left-hand side are images that show them the supplies needed for the class period. This allows them to gather the supplies needed for class and then place their backpacks in their lockers instead of bringing them into the classroom. This is a practice that I learned from Burton Barrager and I’m excited to have been able to start implementing this again with our return to the Middle School building (it wasn’t practical to have them do this in the TALI classroom as there was no place for them to stow their backpacks that wouldn’t be in the way of others).

(2) designs and implements varied activities in each class period

When considering the 70 minutes available to me for each class, I’m intentional about how much I’m trying to have the class do in a given period. With the exception of days where we need the extended time for a time-intensive lab experience, most days I try to have at least a couple of different activities happening in each class to “mix things up” for the students. The activities will be varied, but they are connected. Sometimes that might include a homework review, where students follow a known system for correcting assignments.

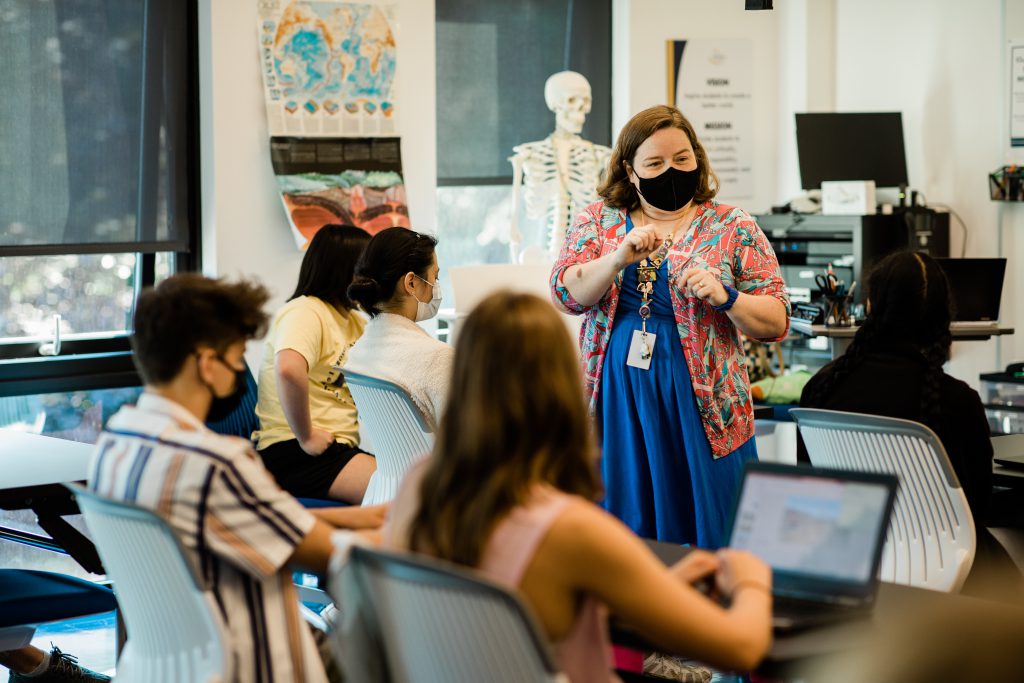

The classroom behavior is quite remarkable. Kids are focused, quiet, and dialed in to the work. This is clearly a result of hard work and clear expectations on KD’s part.

–Anthony Colello, classroom observation February 9, 2022 (more details here)

I look for opportunities for them to collaborate with one another, whether that’s doing a hands-on experiment, or just talking in small groups.

I’m also mindful about not trying to pack too many things into each class period, as transitions between activities take time, and while I want the pace of the class to feel brisk, I don’t want students to be overwhelmed. One example of a class can be seen in the pre-notes for Marine Biology for 2/3/22.

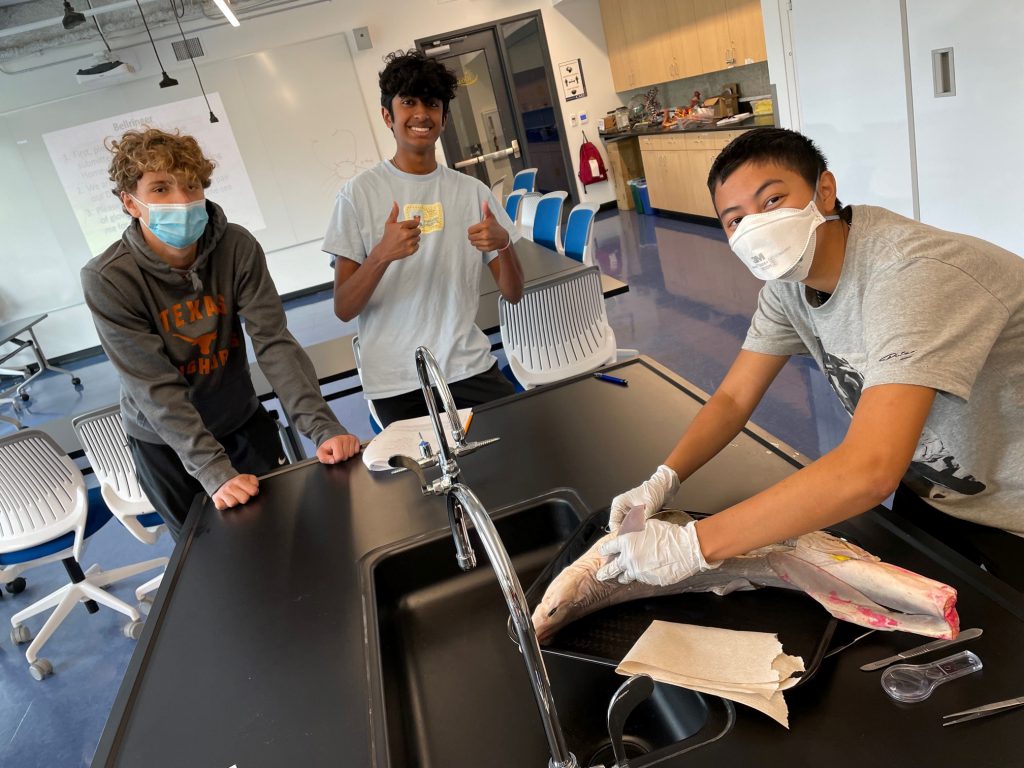

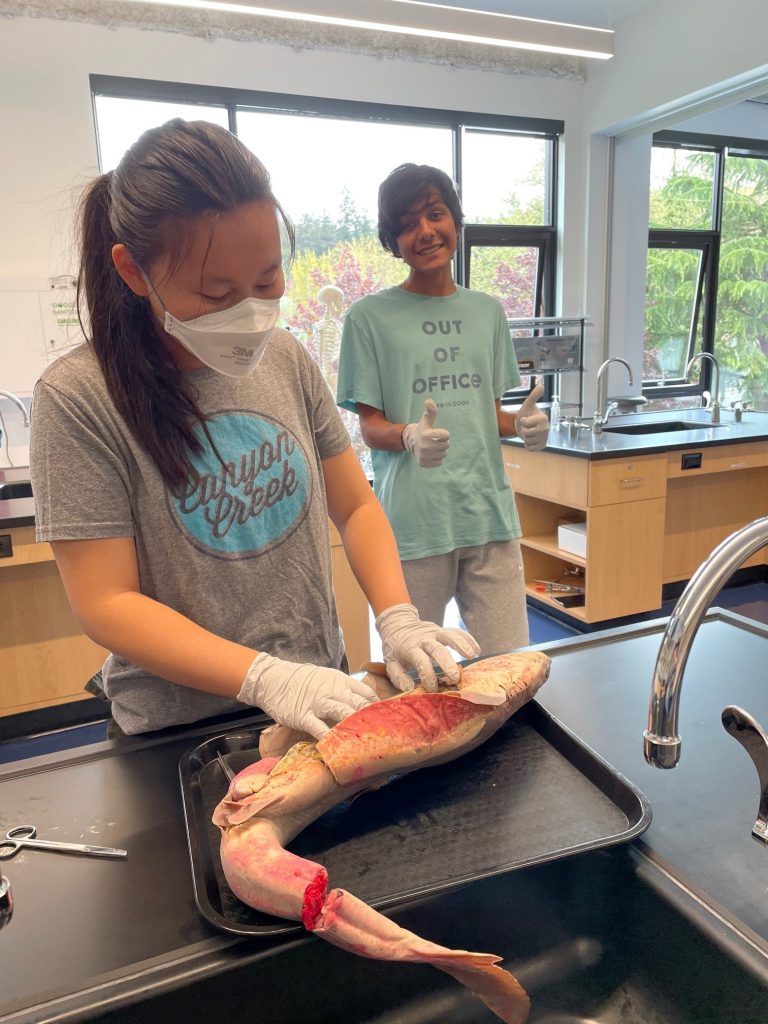

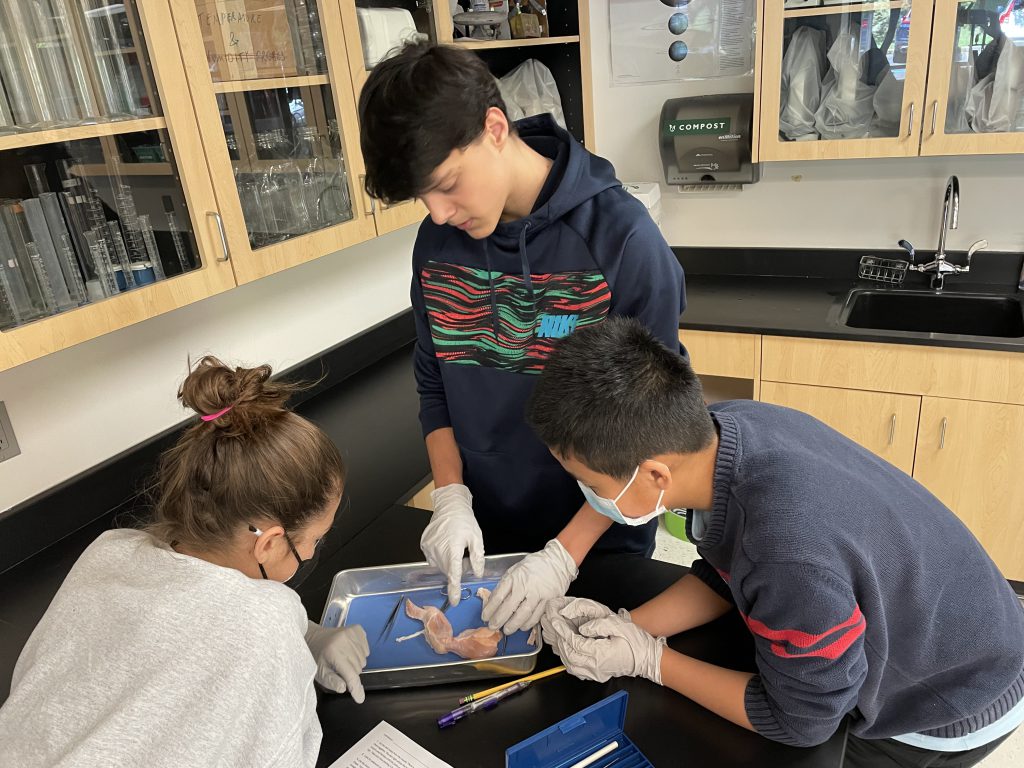

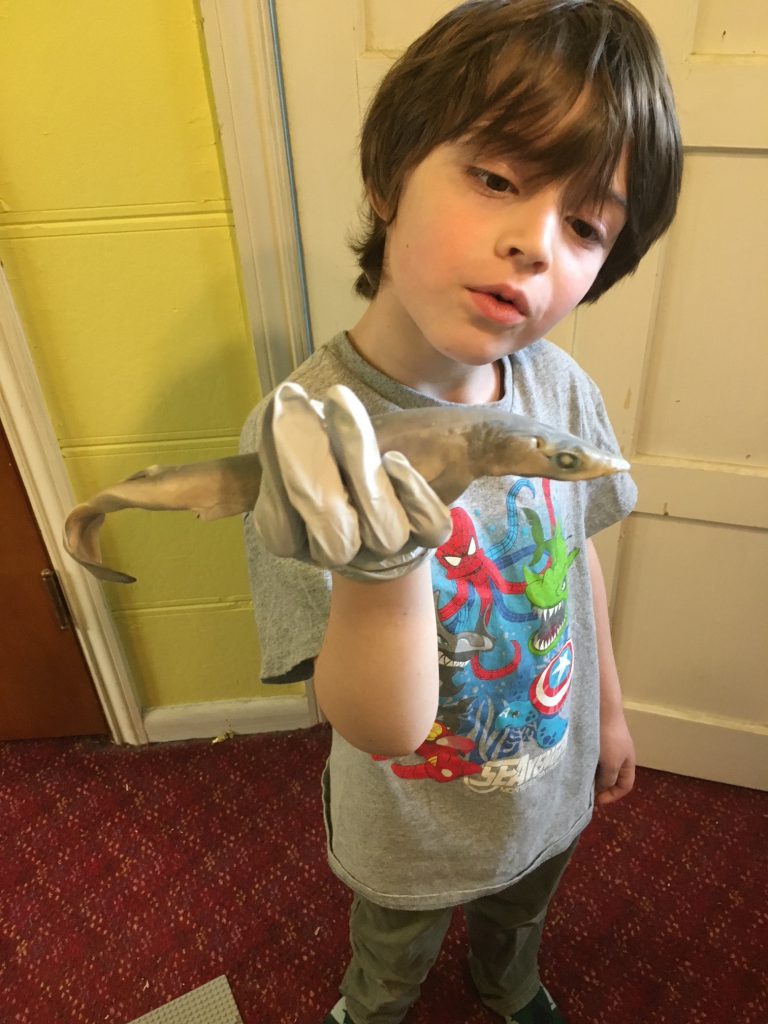

Students started the class period by finishing a dissection started in the previous class (including answering questions). When that was done we transitioned to some brief presentations on intertidal species (students prepared these as homework), and then we finished the class by discussing specifics of our upcoming field trip, including sampling methodology and equipment.

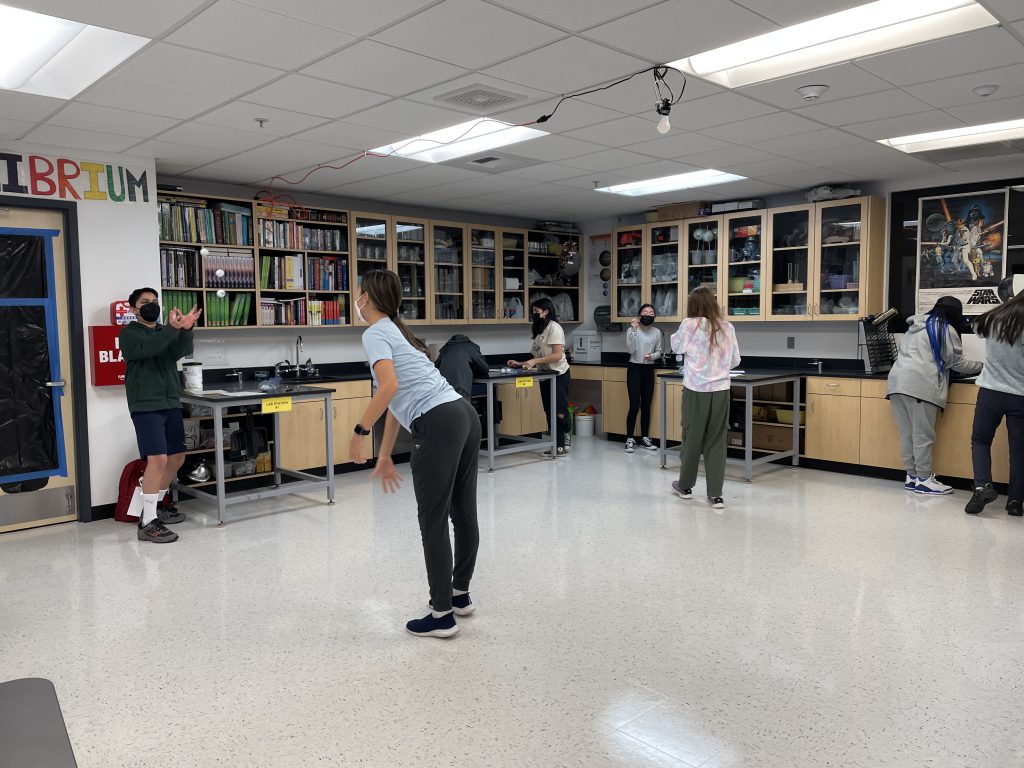

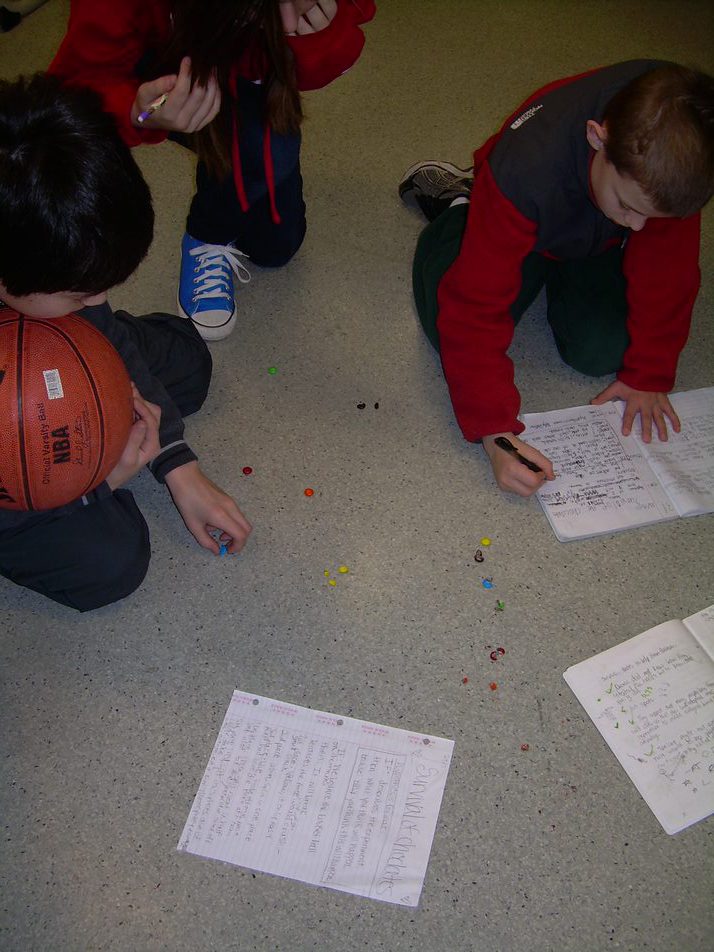

When considering the flow of a class, particularly for Middle School students, I think about building in movement opportunities. Sometimes those are part of the lesson itself, such as the Predator/Prey lab, where students simulate several defensive prey strategies by attempting to catch golf balls (gently) tossed to them by a classmate.

There are some who might question whether or not nine pairs of students can safely toss up to five golf balls at one another, but I have found that with clear expectations, students handle this task responsibly. Their greatest challenge is keeping track of the balls that they don’t catch (in fact, you can see one student looking for a ball under the counter in the first video). They have a lot of fun doing this lab, and it also provides an opportunity to talk about modeling and simulations. Other movement opportunities may be as simple as providing a “stretch break” or “bio break” at certain points during the progression of the class period.

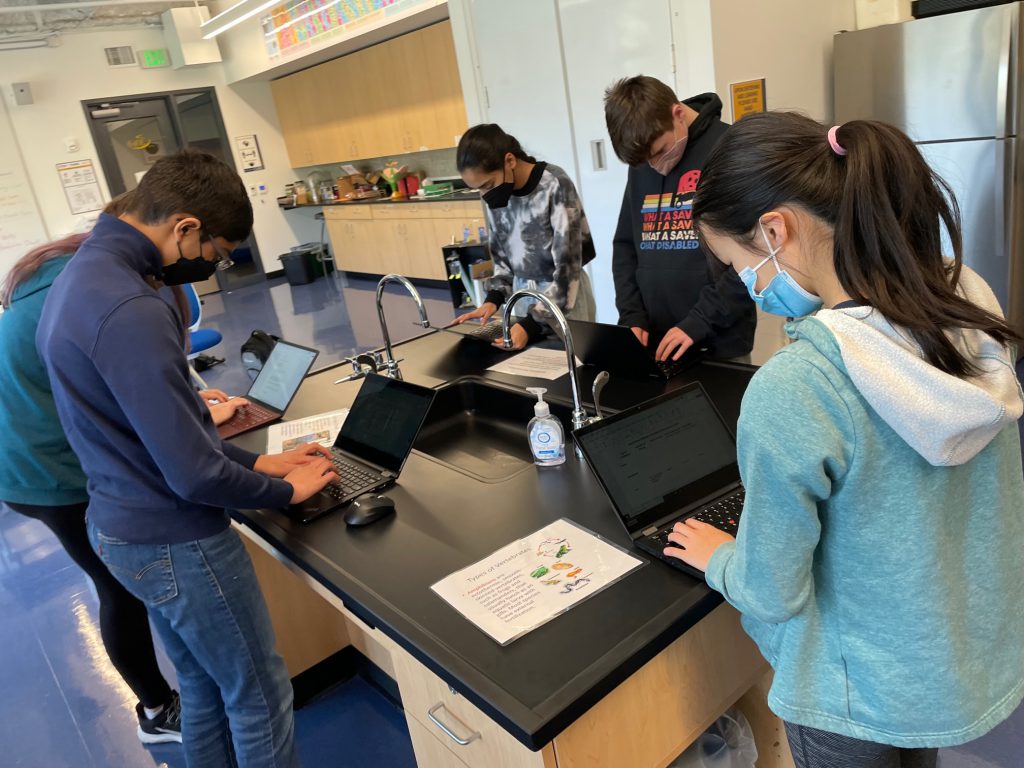

Another specific example I can think of is how I teach information on vertebrates to the 7th graders. I used to do this as a PowerPoint lecture where the students had to take notes and, in essence, fill things in as we went through the information. I found this a little dry, and so I mixed this up into an assignment now called the “Vertebrate Knowledge Quest.” In reality, it’s just the same assignment, with the PowerPoint slides laminated and scattered around the room, but instead of passively receiving information, the students have to move around the room and find the answers to the questions.

The slides are scattered randomly so there’s not a clear progression of which answers can be found where. They’re allowed to help each other out by telling them where they might find the information (e.g., on a slide in a particular part of the room), but not by directly sharing their answers. This gets them out of their seats and collaborating. It also required minimal effort from me to change things up, in that the slides and questions are largely the same, but this allows for a very different feeling in the classroom, as I get to vamp things up by telling them they’re going on a quest and that the “treasure” earned is knowledge. This gets me the predicted groans and eyerolls, but that’s actually what I’m after here–a chance for them to be a little silly but still do some real learning.

(3) brings each activity to closure effectively and transitions intentionally to subsequent activities

I was fortunate enough to attend a Learning and the Brain conference in San Francisco many years ago, and one thing that really stood out to me was the discussion of the mental cost that transitions place on students. At the time of that conference, our schedule had several 8-period days, and I was glad that in subsequent years we moved to an all-block schedule, as that was one way to reduce the mental load that students were experiencing in a day. However, I’m cognizant of the fact that transitions within a class period also have cost associated with them, and for that reason I try not to have too many of them, and to approach them with intentionality and usually a little humor.

I have also learned over the years to be flexible with regard to my planning, and to be more comfortable with the fact that portions of class can take more or less time than I had planned, so I often need to adjust on the fly.

When students are working independently or in small groups, I will typically write on the board at the front of the room how much time they have available (e.g., “Work time ends at _____.”). When we were remote I would put this in the chat for the class so that they would be able to find it later as they worked. In the classroom I will also write instructions on the board for what they should do if/when they finish during the work time. I also give verbal reminders to the class as they work (e.g., “Fifteen minutes of work time remaining!”) to help them keep on pace.

I intentionally wait until I have students’ attention before giving instructions for whatever comes next, and will often say something silly like, “You can show me that I have your attention by turning your beautiful peepers my way.” Depending on the specifics of the task at hand I will sometimes ask students to close their laptops to signal that they’ve finished a particular task, and/or to help remove the distraction of the laptop if I need to give instructions (“I may have lost some of you to computer land, so please go ahead and close your computers now”). In other words, I work to be clear and caring in my instructions–always aiming for that “warm demander” role.

(4) ensures that students are using technological tools effectively

Having been at EPS prior to the adoption of laptops in the Middle School, I’ve seen a lot of change as far as students and technology here are concerned.

One factor in my approach to laptop use in class is whether or not there is a benefit to working on the computer vs. working on paper, as far as in-class assignments are concerned. For assignments that require longer answers, it makes sense to me to have those be digital, as that helps not only students with dysgraphia, but is also a time saver as many students can type faster than they can write by hand.

I am also mindful of situations that may put the laptop at risk, so for many labs I will have students work on paper to avoid having laptops at each lab station, vulnerable to spills or other possible sources of damage.

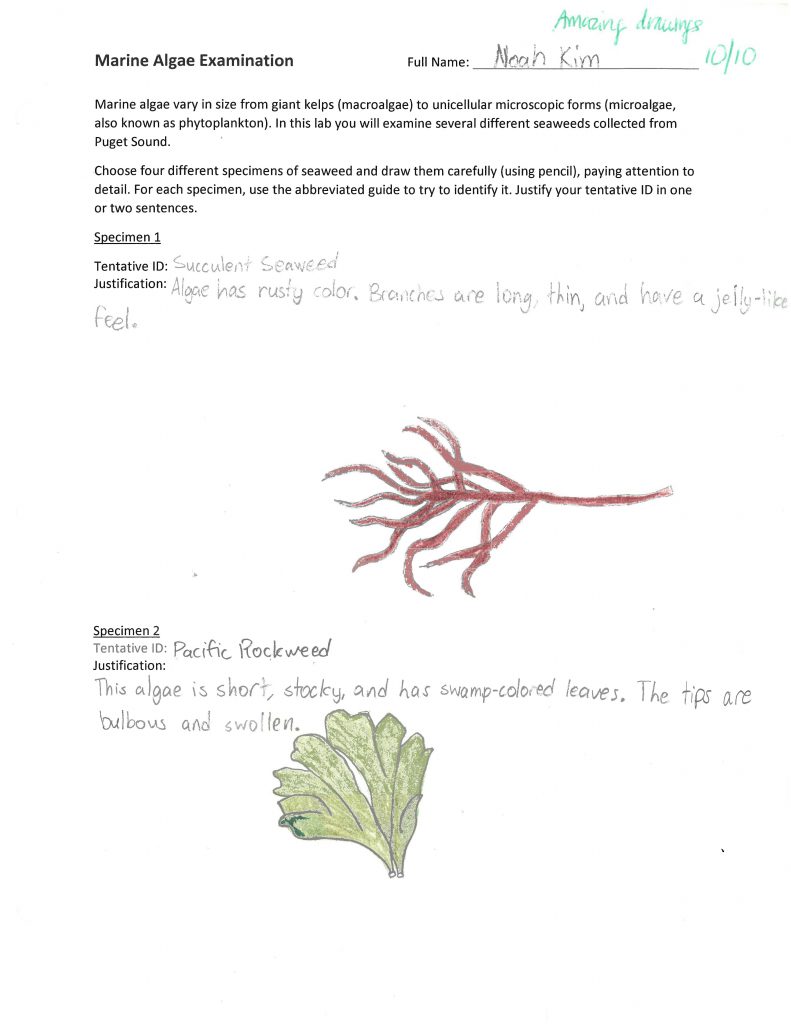

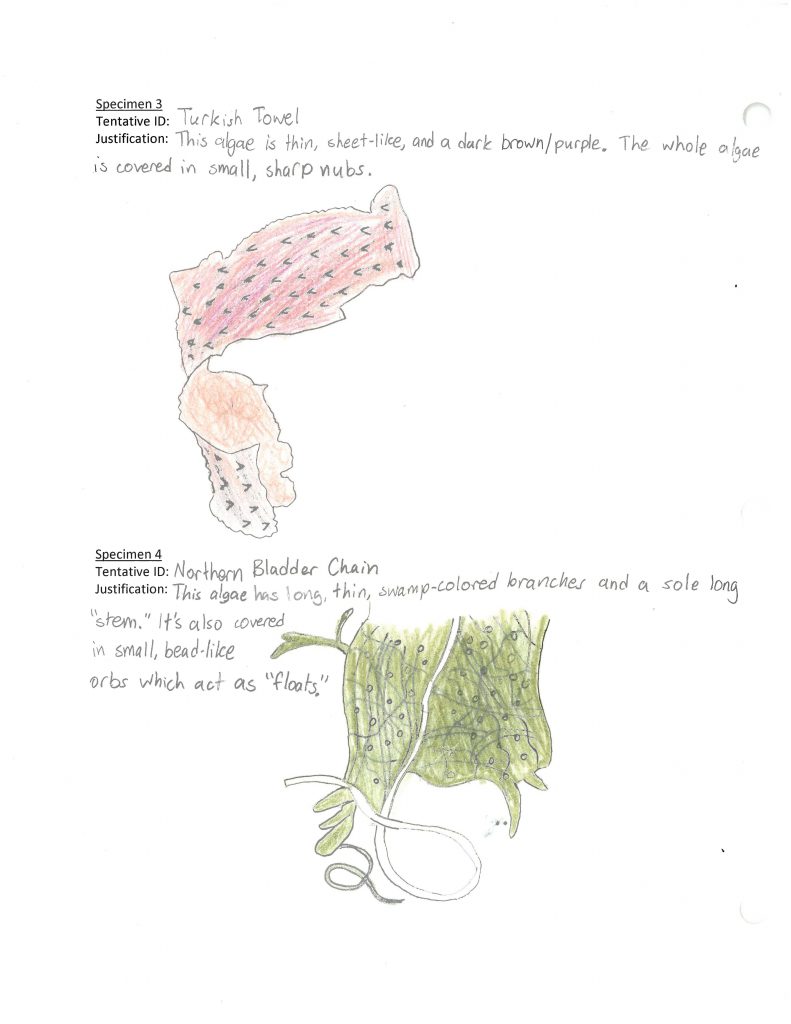

I also ask students to draw some things by hand (including microscope observations or sketches of dissections), as drawing things by hand requires students to refer back frequently to the specimen, and careful consideration of these details helps strengthen their understanding of the relationship of the parts as well as the overall structure.

At the beginning of this school year, when I was teaching the 7th grade in the TALI building, I asked my Middle School classes I to remove their cell phones from their desks or pockets and put them in their bags for the duration of the class period. Now that we’re back in the 7/8 science room and their lockers are nearby, I have a “no cell phone” symbol on the bellringer, asking them to place their phones in their locker for the duration of class.

While I’m sure that there are some students who still keep their phones in their pockets, this sets a clear expectation for them. I would also say that my thinking about student use of cell phones has evolved over the years, and that I recognize that there are sometimes appropriate uses of cell phones within the course of the class (for example, I will allow students to listen to music during certain work time). But I continue to push back a little on cell phones in class–just the other day I had a student ask if they could get their cell phone so they could time an experiment. What was particularly amusing was that the student asking that was literally holding one of the classroom stopwatches in their hand at the time. I gently pointed out that they already had a timing device, and they accepted that without any pushback.

For those times when students will be on their computers, I have several practices that attempt to help them remain on task. When we are transitioning to the computer I encourage them to take a moment to consider if they have anything open on their computer that might be a distraction to them, such as a game or a browser window, and encourage them to close them. Again, I don’t think that this is foolproof, but it’s more about clearly establishing my expectations around tech use while also encouraging them to have some ownership, as they are the ones who are asked to decide whether or not something is a potential distraction. I also position myself frequently at the back of the room when students will be working on their computers for any length of time (such as when we review a homework assignment). The first time I do this I ask the students if they have any thoughts about why I’m standing at the back of the room, and one of them always points out that this is so that I can see their screens. I agree, but again frame this as another way of encouraging them to make appropriate choices while we’re on our computers.

I have a different approach in my Upper School classes, as these students are at a very different point developmentally. I still have an expectation about appropriate tech use, but don’t police their behaviors. To my mind, it’s important for these older students to get more practice in self-regulating around their technology use during class, as they will be off at college in a few years. They need a chance to figure out what works for them, on their own terms, and as long as they are generally engaged and showing good depth of thought in their assignments, I don’t feel that they need the kind of scaffolding that I use with the middle schoolers. In essence, it’s about allowing them to control these behaviors intrinsically instead of relying on external factors that I provide.

(5) concludes class with a summary and clear tie-in to the next class

In my first few years of teaching, I didn’t have much intentionality about the end of class, and things were always a little chaotic. I had a light bulb moment about this after observing Michael Connelly, a Spanish teacher who was here at EPS for a couple of years and had many great ideas about classroom practices.

Following his example, I developed a predictable end-of-class routine for my 7th graders, where I intone, “You can show me you’re ready to go by standing up and pushing your chairs in,” which is followed by students waiting at their spot to be dismissed by name. This leaves the room in good shape and also gives me another opportunity to affirm each student by calling them by name (although on occasion I do dismiss by table groups or rows).

Beyond that, though, I don’t spend time, particularly at the end of class, talking about what’s coming up in the next class, although I would say throughout class there are references peppered in to what’s preceded our current work as well as discussions of how this will connect to future content. Prior to engaging in this PDP, I didn’t really think about this indicator as a goal of my teaching. Now that it’s been raised in my awareness, I would say that this is something that I would still not choose to emphasize, primarily because I want to preserve as much time as possible for “doing science.” Particularly with 70-minute class periods, time is precious, and I don’t want to lose even five minutes on something that doesn’t enrich an in-class experience. I can also admit that it’s something that I haven’t done because I haven’t done it–I don’t have a reference for what that might look like, and prior to considering this indicator it’s not something that I’ve really thought about. That being said, there are references available (such as pre-notes) for students who wish to look ahead to the next class.

Differentiated Instruction & Assessment

One of the most rewarding aspects of teaching at EPS are the smaller class sizes, which really allows teachers to get to know the students in their classrooms. On top of that, having a robust Learning Support group means that I can get assistance in connecting with each student in the most effective ways.

(1) considers and addresses each student’s learning profile

In order to help students succeed in my classes, I have to get to know them as individuals. This includes learning about how THEY learn. The first way I go about this is by attending the grade-level kid talk sessions at the start of each school year.

I take notes as information is shared about students so that I can be informed of any sensitive areas or necessary supports before they enter the classroom.

I also look on four11 to see the accommodations for all of my students and read any available learning plans.

Throughout the year I coordinate extensively with our Learning Support program. I meet with students to discuss quizzes and encourage those students with accommodations to give them a try if they haven’t used them thus far (an example can be found in this email).

I keep an eye on how students are doing in class and reach out to Learning Support to discuss individual students if I have a concern. In fact, I’ve recently worked to connect one of my 7th graders with Jamie Andrus to talk more about studying. This student is a hard-working and engaged student who struggles on assessments. Right now she believes this problem is unique to Science, but anecdotally other teachers share similar observations, so I felt it was important to try to connect her to Learning Support for broader support.

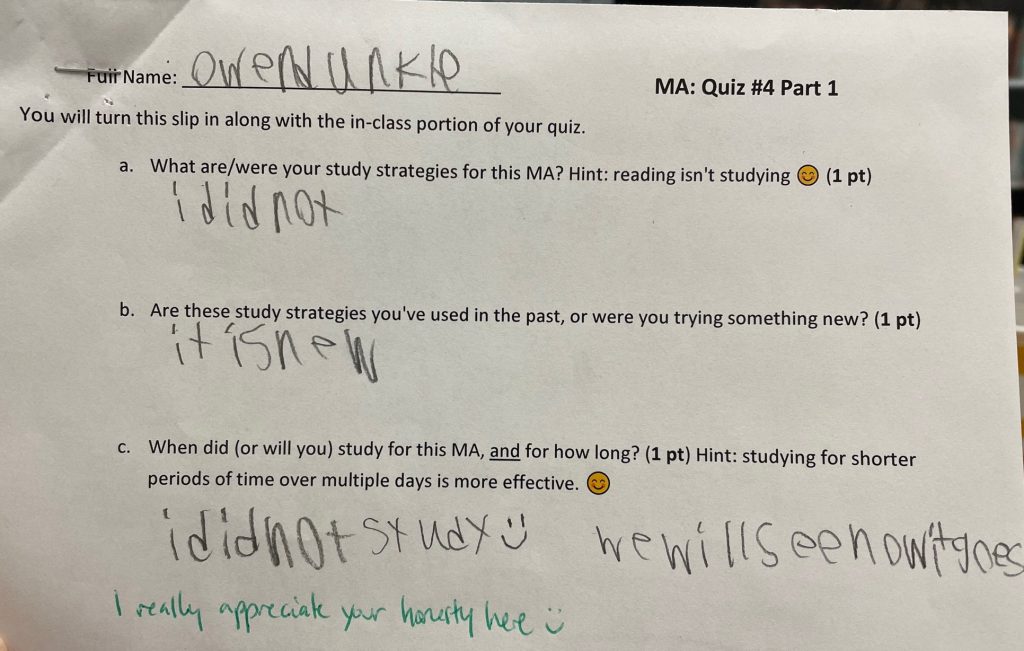

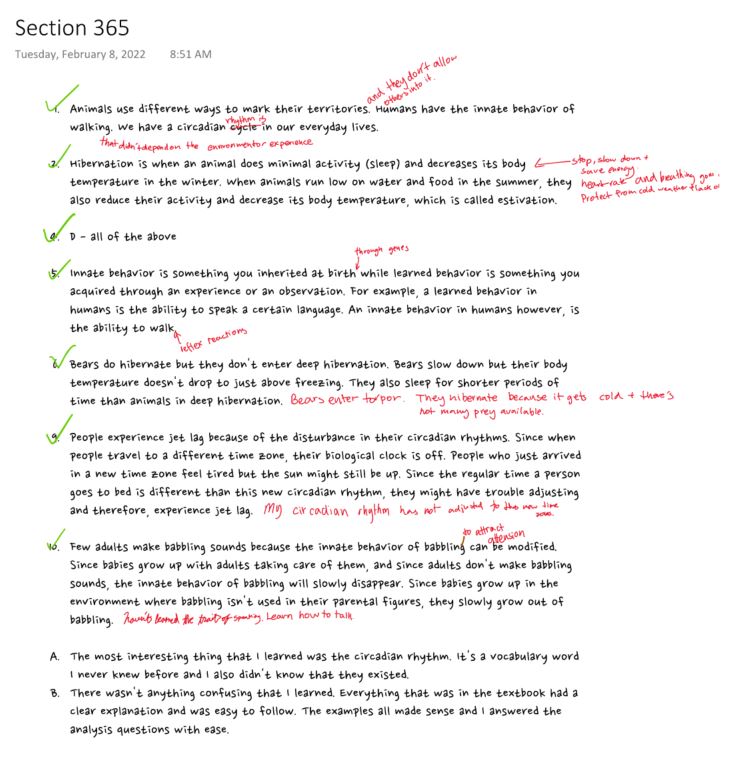

A change I have made in winter of 2022 relates to testing and study strategies. I used to have individual conversations about these with students after quizzes, particularly ones that they found difficult, but conversations with Jamie Andrus helped me think about this a little differently. Since one of the reasons I give quizzes in 7th grade is to give students an opportunity to practice and refine study strategies, I am now emphasizing that as part of the actual quiz grade, with questions asking specifically about what students did to prepare and how long they spent on that preparation.

There are no “right” answers to these questions, and students get the points even if they say they didn’t study, but my hope is that by putting greater focus on the process, students will reflect upon what they’ve tried and get a better sense of strategies that help them succeed.

(2) designs class activities and assignments that engage and accommodate for both individual students and a diverse group of learners

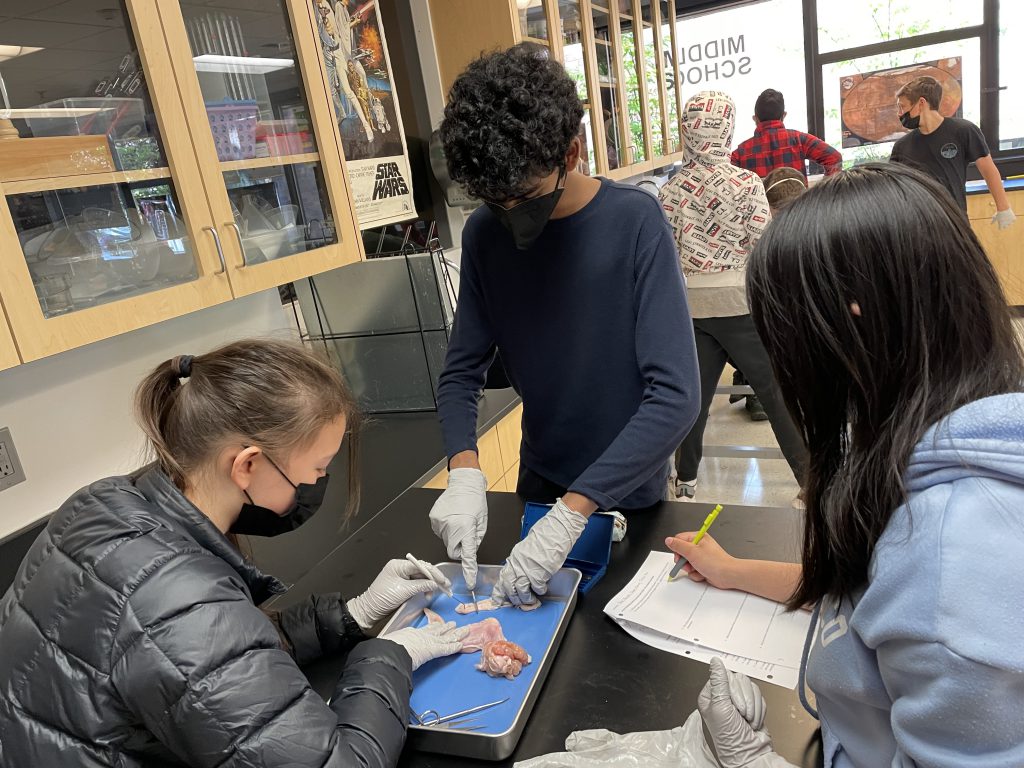

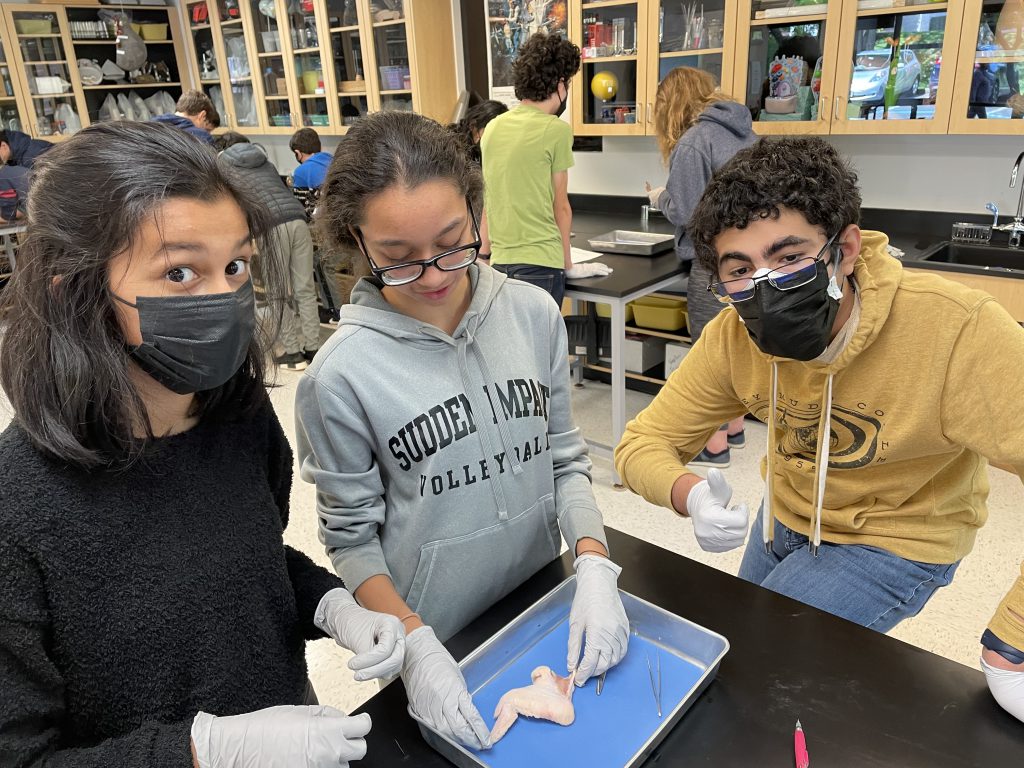

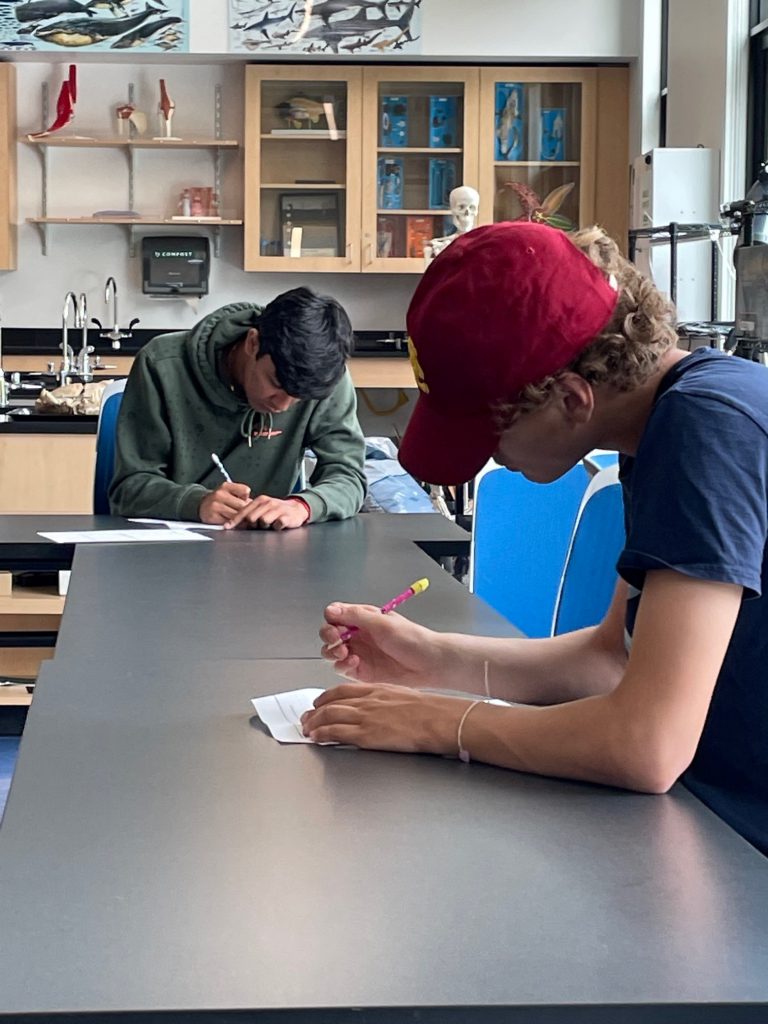

On a day-to-day basis, students frequently work in pairs or groups of three in my classes. Having students work in groups allows them to learn from one another and also makes it possible for me to circulate among them, observing and providing assistance as needed.

This allows students to work at different paces, and also allows me to teach what is needed in the moment to these small groups, whether that’s clarification of information, tool use, etc. Sam Uzwack observed this in a dogfish dissection lab in my Marine Biology class, and pointed out that there were some students who were finished with the hands-on portion but those students were still on task, working on some of the questions in the lab.

I also strive to have things available for students to work on if they finish the task at hand during the allotted work time. The way I think of it is that I have them for only 70 minutes, and I want them engaged in Science for the duration of the period. I tell them, “I want you doing Science in Science class.” That might include getting started on a homework assignment, working on a longer-term MA, or watching supplemental videos online that connect to the topics we are studying.

I’m intentional about not making it an additional assignment, as over the years I have observed that many students are very sensitive to whether or not something is perceived as “extra work,” and I don’t want it to come across as, in essence, a penalty for working quickly.

While they gather data and make observations together, most assignments are still submitted and graded individually so there is accountability to what is happening in class. In 7th grade there is a partner presentation, and for this assignment I pair students using a strategy that Kelly Violette shared many years ago. Students are partnered based approximately on their grade in the class. I am open with them about why they are paired this way (while of course not revealing the pairs in any sort of grade-based order), and acknowledge that having the same grade doesn’t necessarily reflect the same level of effort and interest, but that all students tend to do better work when partnered this way. In my experience, the high-achieving students express gratitude that they are partnered together, and the students who may struggle a bit more actually engage with the process and produce good results as well.

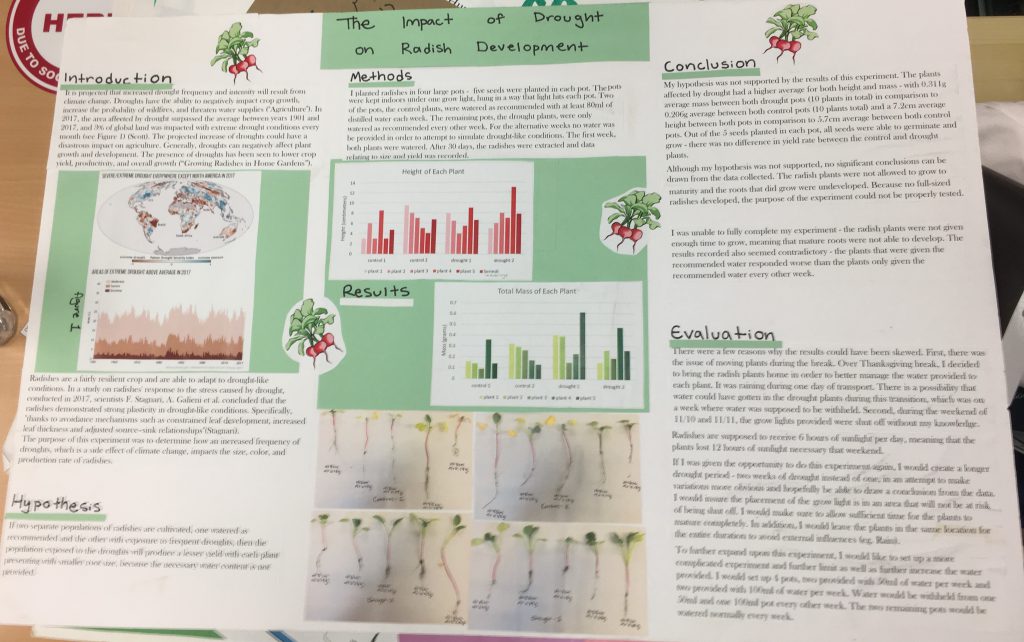

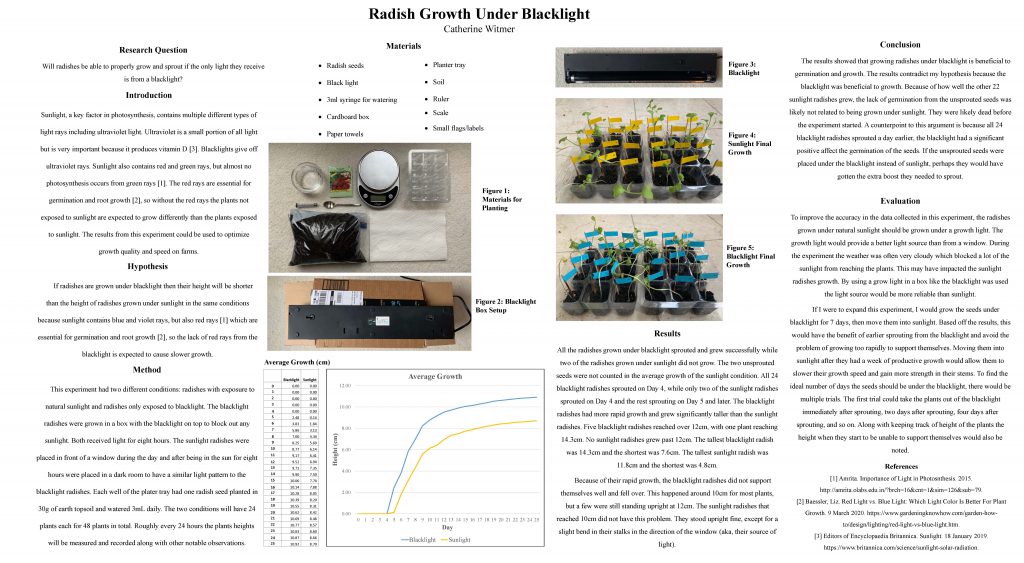

When I think about the MAs in my classes, I intentionally create a variety of assessments to give students opportunities to show their knowledge in different ways. These include lab write-ups, quizzes, presentations, posters and symposia.

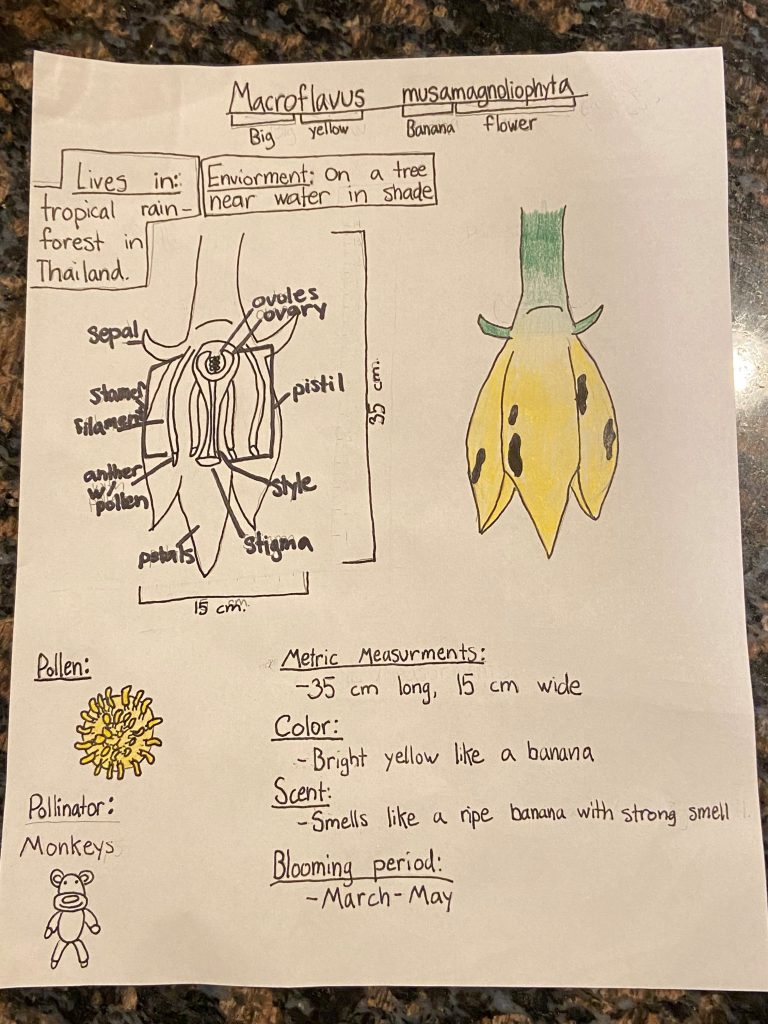

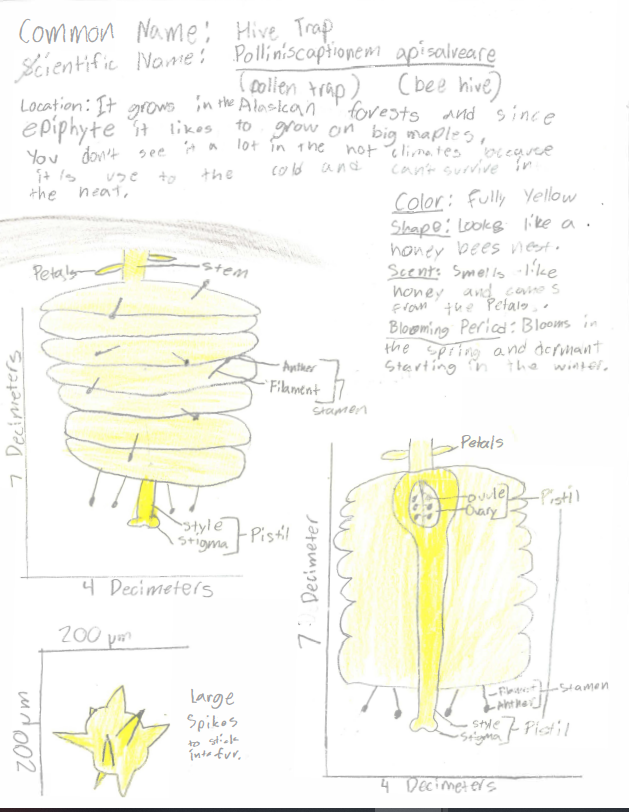

Several projects in Scientific Thinking 2 provide students with the chance to stretch their creative/artistic skills as well, through the model they build (and the video they create) for their Cell Analogy Project as well as their Flower Discovery Project.

At the same time, it’s not a requirement (or even a portion of the grade) that students engage artistically with these assignments, so there is flexibility and choice involved.

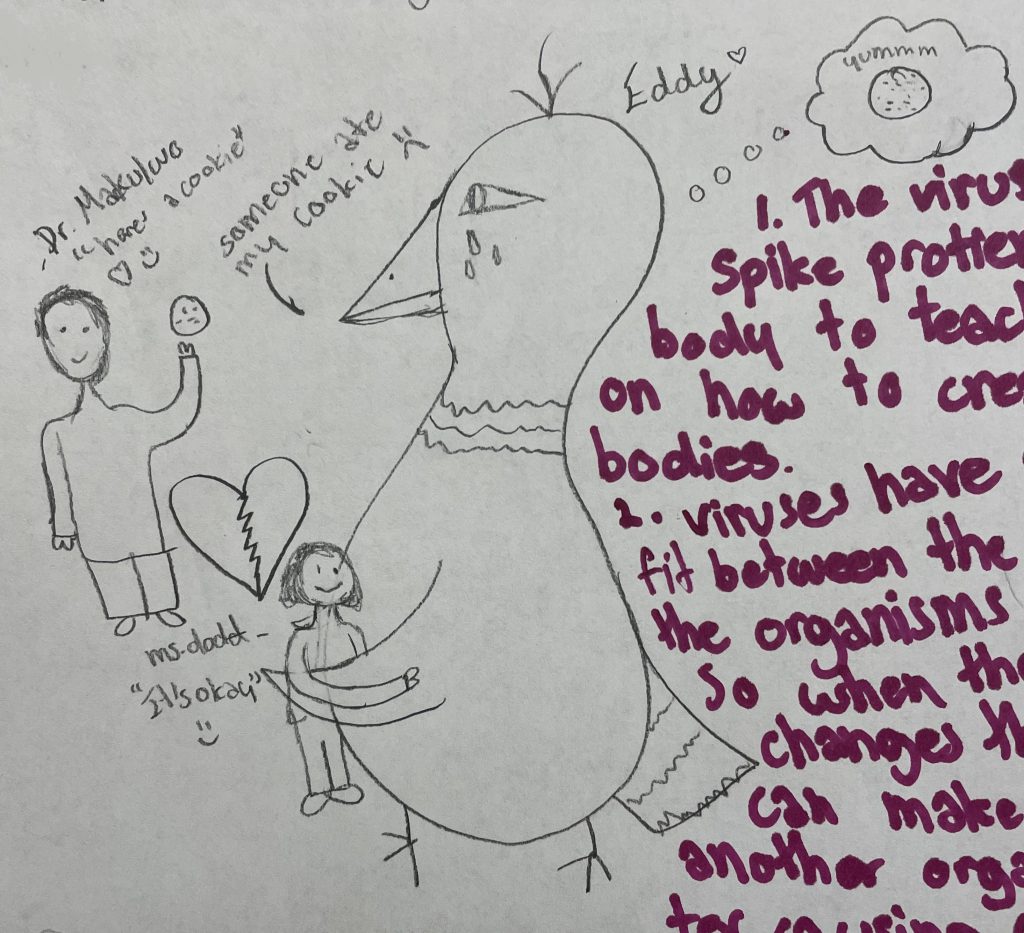

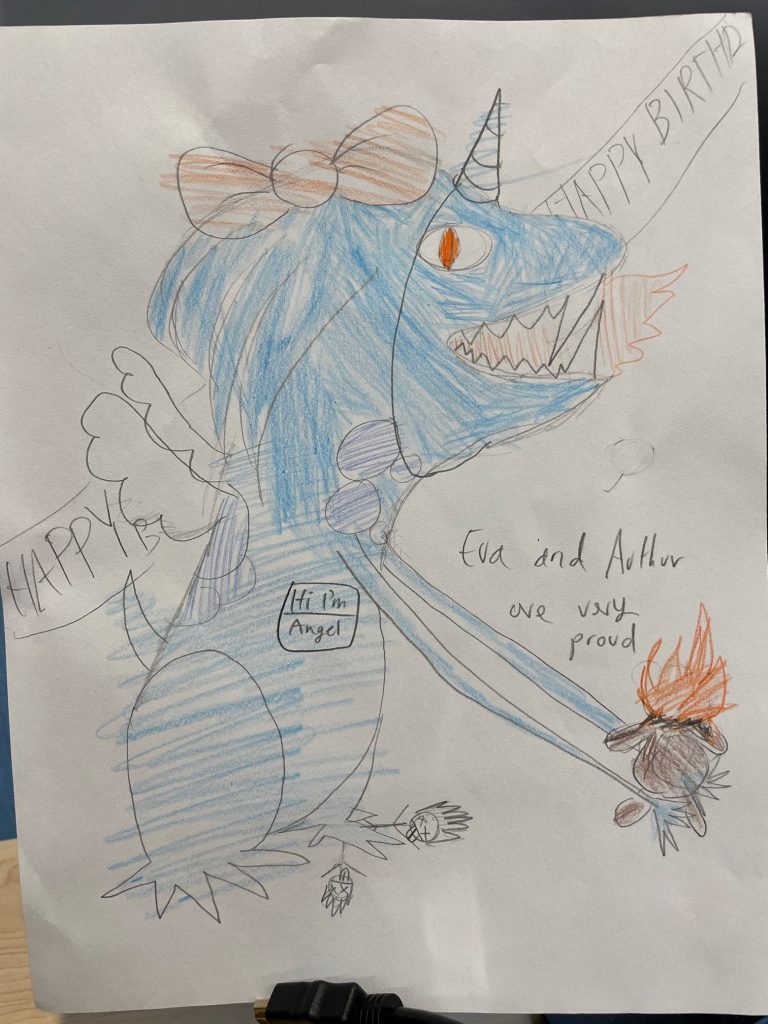

And there are other, smaller-scale opportunities where students can bring their artistic talents to the table, if they so desire.

For my Upper School trimester courses, I wanted to have assessments that were similar to what students would experience in collegiate science courses (scaled down a bit to a high school level). I write challenging tests that ask students not only to retain but also to apply concepts. Several students have said to me that the tests are more difficult than they initially expected, but that they also felt that the tests really assessed their knowledge in a way they hadn’t previously experienced.

In Ecology, students finish the trimester with a “long-term” (e.g., three to four weeks) study of their own design. There are specific expectations for their experiments in terms of number of replicates and they get feedback along the way as they work individually or in pairs to execute their plan. They create a scientific poster and present their findings in a round-robin style symposium meant to mimic a poster session at a scientific conference.

As mentioned previously, I wanted to go another direction in Marine Biology, so the students in that class write two scientific papers on a species of their choosing. The first is a Literature Review, where they use peer-reviewed sources to summarize the current state of knowledge on their organism. They then build upon this information to write a Grant Proposal to answer a currently unknown question about their species. Students then evaluate the proposals of several peers and decide how much funding to allocate to the proposed studies. These assignments provide students with an opportunity to engage in a writing style that is different from what they’ve experienced in most of their other classes.

(3) builds in opportunities for each student to contribute during each class period

In my 7th grade class, I have an expectation (reflected in their weekly responsible action grade) that students participate when we review a recurring type of homework (called a Section Review). I have labeled large popsicle sticks with each student’s name and refer to these as the “Sticks of Choosing” (a silly D&D reference).

When we review the assignment, students raise their hands if they want to share an answer. I make a note of whose hands are up then draw from the Sticks of Choosing to see who gets to share their answer, and once they’ve shared their answer their stick is set aside. This helps ensure that different voices are heard throughout the class period.

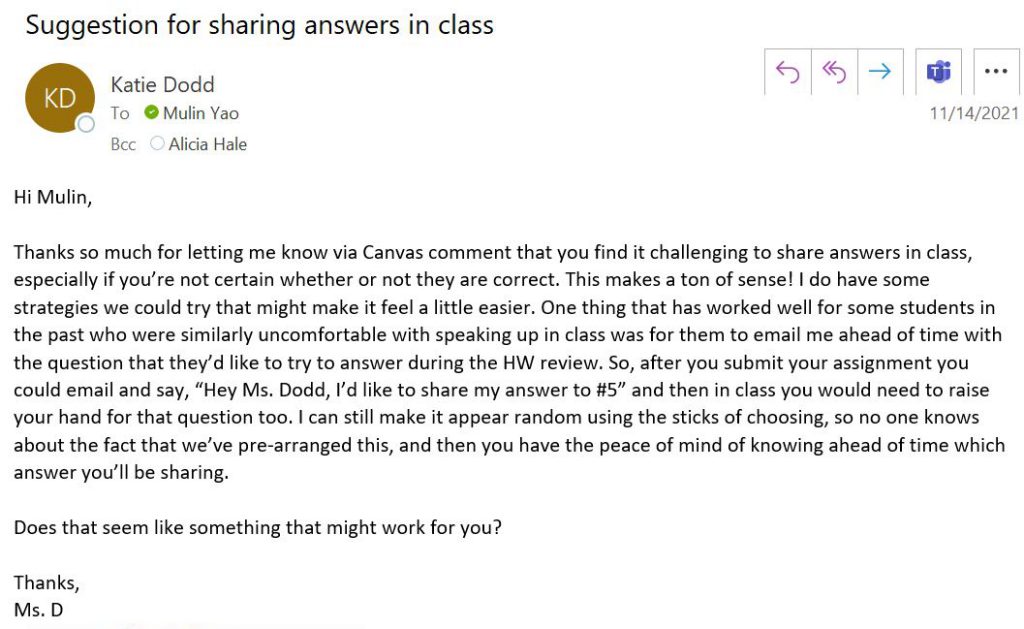

For some students, though, speaking in front of the whole class is a very challenging “ask.” I make a point of reaching out privately to students who don’t raise their hands to discuss some potential strategies that might help that feel a little easier. One approach that has worked for a fair number of students is for them to email me ahead of time to tell me which question they would like to answer. Although we’ve prearranged things “behind the scenes” I still make it seem as though their name is drawn randomly via the Sticks of Choosing.

Knowing which question they are answering helps lesson the anxiety for some students. Being able to choose to share an answer in which they feel confident seems to help; many of the students who don’t like to speak up in class share that the main reason they don’t want to do so is that they’re worried that their answer is incorrect. Over time, many students who use this strategy initially find it a little easier to share their thoughts and sometimes they stop emailing me ahead of time and start volunteering on their own, which is cool to see. On top of that, since students frequently work together in groups of two or three in this class, this provides everyone with an opportunity to contribute within those groups. I have noticed that even students who may be reluctant to speak up in front of the larger group will do so if they’re talking with only one or two others, and in this way they are sharing their thoughts and contributing to the conversation.

When we were remote I frequently used an attendance question to try to ensure that I got to hear from each student at least once during the period.

These were usually silly questions, so they were fairly low stakes for most students. I would typically start with the volunteers and then ask students who hadn’t volunteered if they felt comfortable with sharing their answer, although they did have the option to pass. This is not a practice that I have continued when we’re in person, largely due to the time it takes and my reluctance to lose that as “science teaching” time.

A change I have made recently is based on some information and tips that Jamie Andrus shared with the faculty during comment-writing time. I used to encourage quiet students to look for more opportunities to speak up. Jamie pointed out that this is not the sort of thing that encourages introverted students to speak more often in class. I have now changed my comment phrasing to ask if the students are interested in exploring ways to join the conversation more frequently rather than assuming that this is an area that needs addressing.

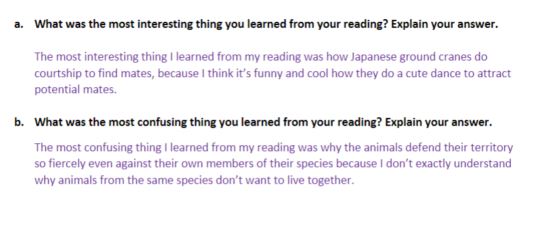

(4) provides alternative explanations of course concepts

In my 7th grade class, students have a recurring homework assignment (called a “Section Review”) where they read a section of the textbook and answer questions about the material. I think of this as a kind of formative assessment that is meant to introduce them to concepts and get them thinking about things. Their assignments are graded on completion, not correctness. As part of the assignment, students are asked to explain what part of the reading was most interesting and what part was most confusing (and why). This helps me get a sense of the areas that likely need deeper review.

We discuss the questions in class and students are expected to correct and add on to their initial responses and then resubmit the assignment.

While reviewing, I project my OneNote onto the board and serve as a scribe for the answers that they share. This way, students can hear the answers out loud and also read them on the board. I do not archive the answers that I scribe, as I want to incentivize students’ engaging in this conversation in the moment, and I suspect that if they knew they could see the correct answers later, some students would check out of the process. On rare occasion, though, Learning Support has asked me to share corrected answers so that they can use them while working with a student in GSH, and of course I provide them in those instances. When I grade the assignment, I comment on what each student indicated was most confusing to them, offering to discuss it further (though it must be said that I am taken up on this offer very infrequently–hopefully because the intervening discussion has helped to clarify things).

These textbook readings are then connected to other activities and assignments that we do in class to reinforce concepts. For example, when learning about osmosis (see evidence for all things mentioned in this paragraph), we start with a discussion of why osmosis matters–why should students care about something that initially seems important only on a cellular level? I share the (true) story of the woman who died after participating in a water-drinking contest held by a radio station (“Hold your wee for a Wii”). We then review the textbook assignment that introduced some of the more technical aspects of osmosis. Next, we do a lab using eggs to provide quantifiable evidence of osmosis in different liquids. Students generate hypotheses about what will happen to those eggs in different solutions. I have an osmosis PowerPoint posted to Canvas that they can reference to help them make these predictions (but as is always the case, it is clearly stated that they won’t lose points if their hypotheses are incorrect). In many cases, those predictions still indicate some confusion around the process, so the “unexpected” results are a surprise.

Working through those results and answering the analysis questions helps students put the pieces together. After I read through the students’ answers to those questions I have a sense of where any points of confusion may lie. We debrief the lab collectively by watching a video (also available to them via Canvas) that describes what happened to their eggs, (including animations of what was happening at the molecular level). The combination of these different approaches allow students to engage with the information in a variety of ways, including a hands-on component, and this helps to clarify the content.

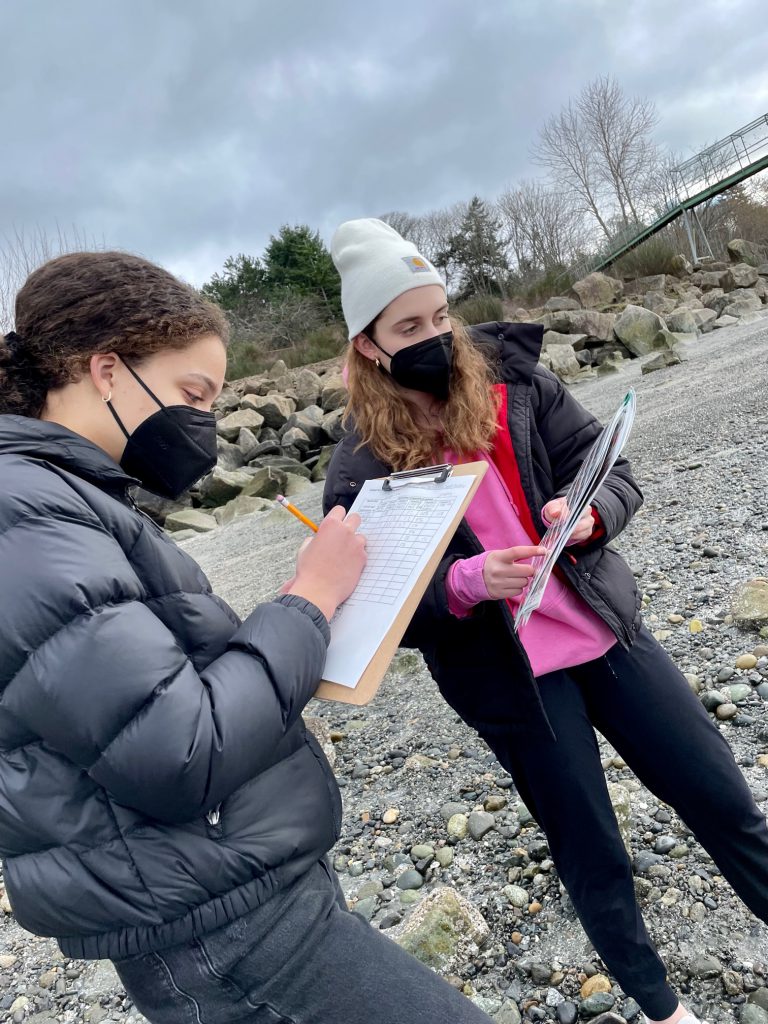

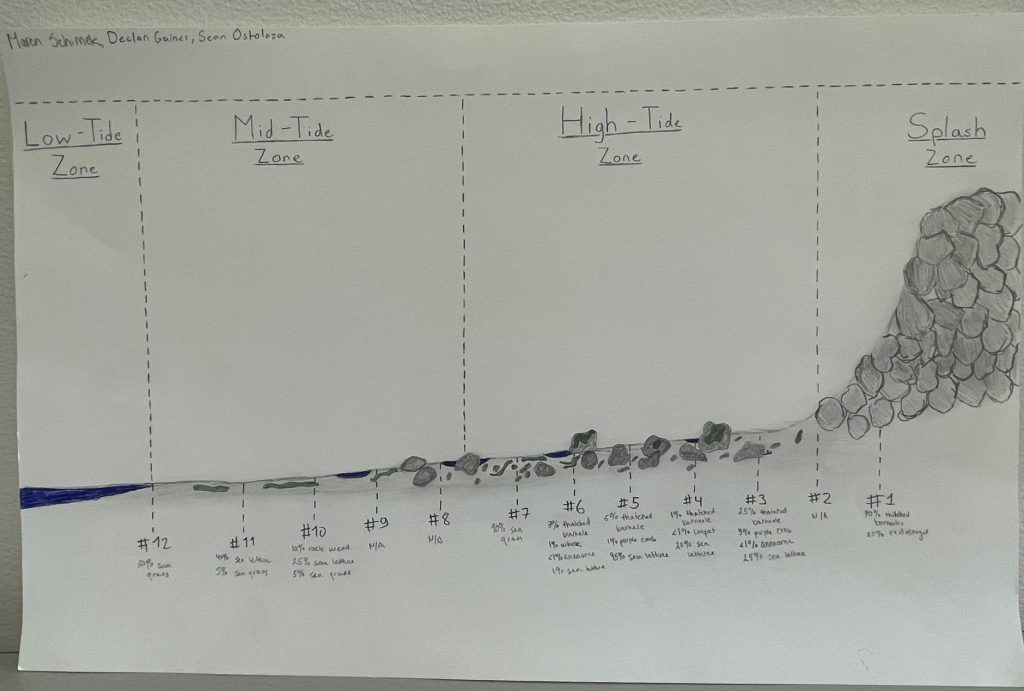

In my Marine Biology class I have had several field trips that provide another way for students to connect with course content in an intentionally experiential way. There is a balance to be struck, though, since these field trips require students to miss a neighboring class period, so I have to be somewhat judicious in my planning. The field trip that I’ve done most often is a visit to a Puget Sound beach where students conduct fieldwork to sample intertidal organisms. Prior to the field trip students learn and teach one another about some common intertidal species, and I also discuss the sampling methodology that we will use (see evidence for documents).

At the beach, students work in teams to conduct quadrat-based research along transects, where they identify and estimate the abundance of different species. They have several field guides available to help them with their identifications, and they record their information on a provided data sheet. This is a type of study done by field ecologists, so it’s an opportunity for them to conduct “real science” in an outdoor classroom. It’s amazing to see how engaged the students are on this field trip–even seniors jump in with enthusiasm.

The next class day they complete a post lab, where they sketch their transect and summarize trends and adaptations seen in the species.

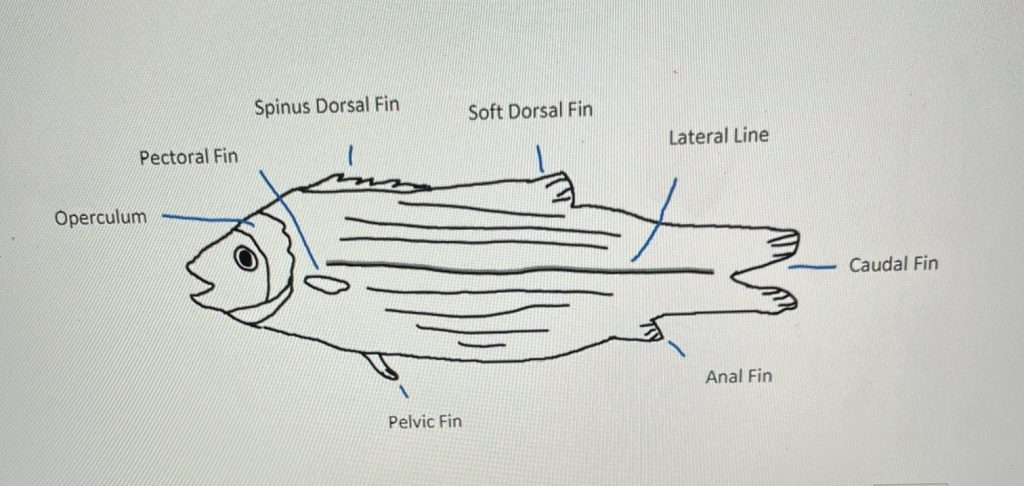

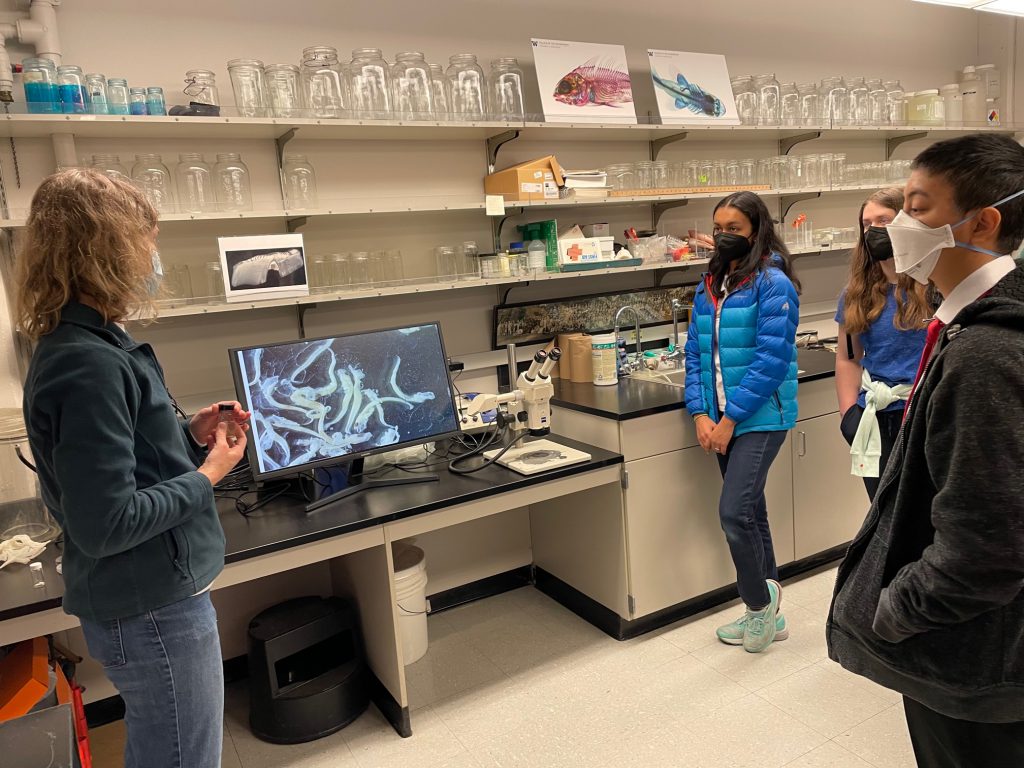

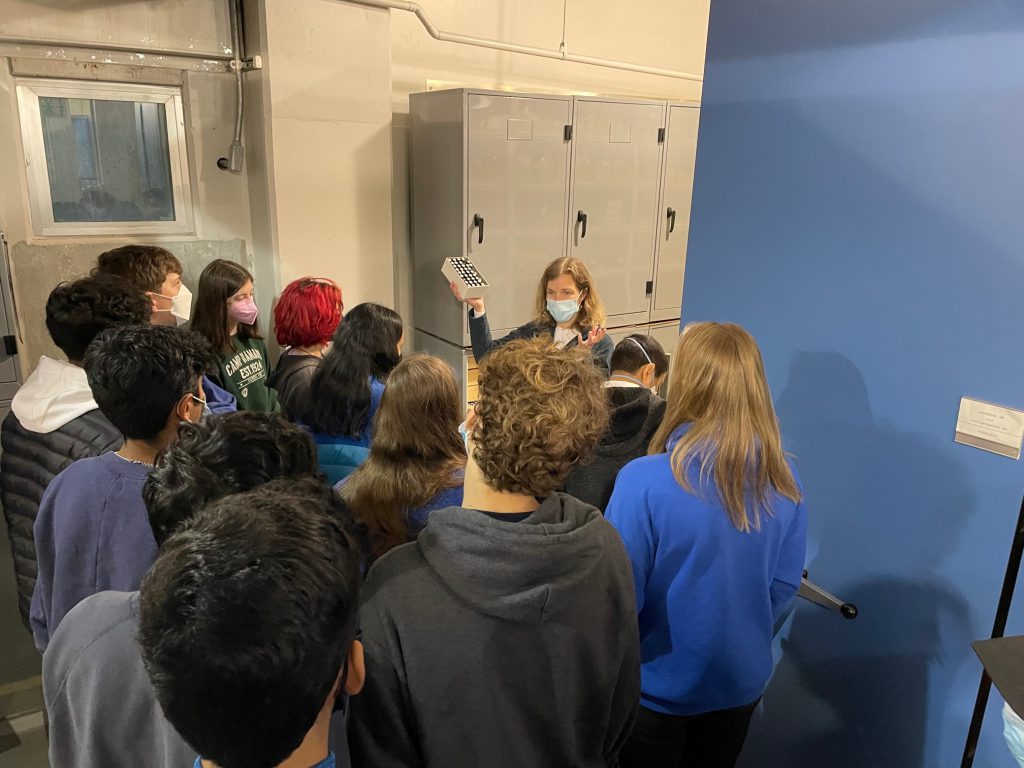

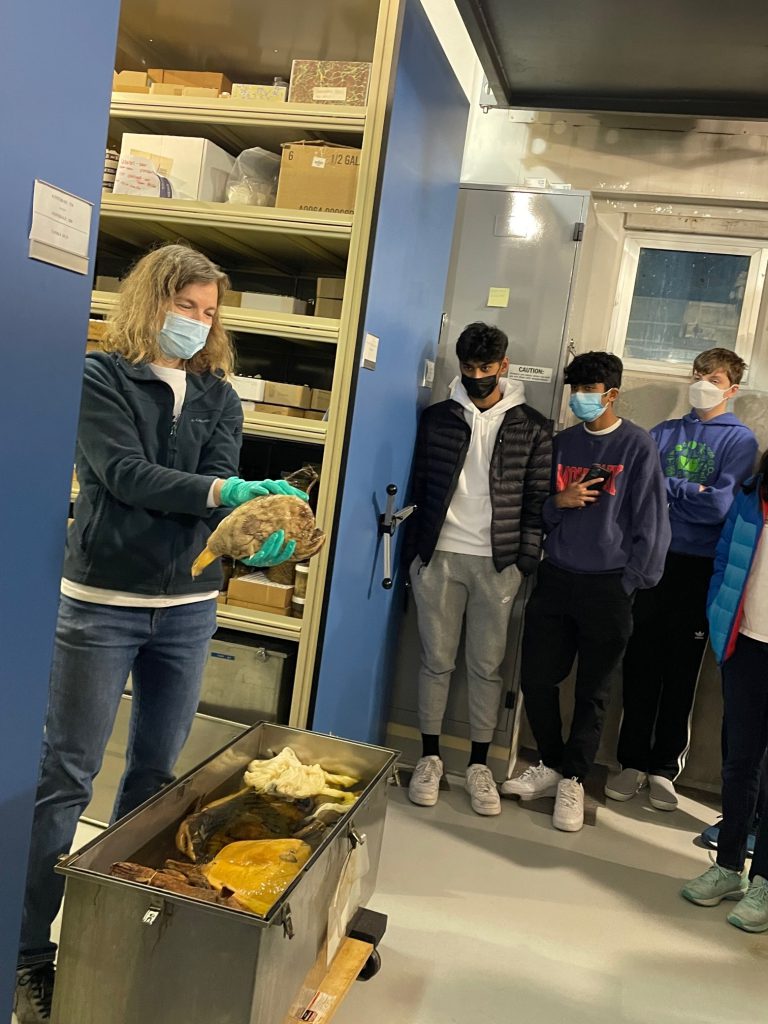

I’ve also taken Marine Biology students to the Fish Collection at the University of Washington (associated with the Burke Museum, but in another area of campus). I have a connection here as this was the lab I was in as a graduate student, so they are typically very accommodating. This not only allows them to see real specimens of a variety of species (including sharks and deep-sea fishes) but also gives them a sense of some of the current science of ichthyology, as well as possible academic or career paths. We weren’t able to go on this field trip in Winter 21-22 but fortunately Covid restrictions were eased a bit and the spring trimester class was able to go.

All of these field trips come with a cost in terms of the time and energy spent planning and coordinating logistics, as well as the previously mentioned impact on other classes, but to my mind they offer such a meaningful and genuine opportunity for students that they are well worth it. After our most recent trip to Carkeek Park for the intertidal study, several Marine Biology students thanked me for the field trip and said it was both fun and educational.

(5) adapts instruction based on formative assessment

Building off of what was mentioned in the previous section, I use the textbook readings and supplemental questions as formative assessments, and these help me get a sense of student understanding as we continue to work on a concept. The conversations that arise during our review sessions are another opportunity to engage with students on what they know and where they are. For example, in going over questions about animal behavior, we discussed jet lag and several students were able to connect their lived experiences to the idea of a biological clock, something they may not have realized prior.

This year I have started to give occasional ungraded check-ins at the start of class (currently ridiculously called a “show me what you knowie” to emphasize that these are casual and not something that students should stress about).

Students are asked to answer questions related to concepts we’ve been covering. These provide students with a good check-in about their own understanding (as well as how they are retaining information on a day-to-day basis), and are helpful to me in seeing where they stand with course content.

I also look for opportunities to adapt instruction to connect to real-world examples and student interest. For example, the way that I have taught the immune system to 7th graders has changed significantly with the COVID pandemic. In spring of 2020, which coincided with our going remote, I provided a fairly open forum for students to submit questions about COVID and researched and answered those based on our current understanding of the virus. In 2021, we spent more time focusing on the origins of the pandemic (as known at the time) and then did a deeper dive into the development of the vaccines. These were topics that were always covered in ST2, but being able to connect them to our lived situation helped student engagement.